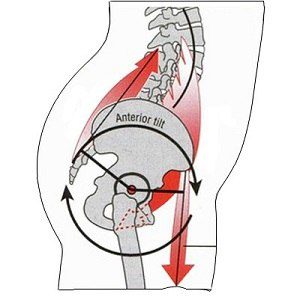

Anterior pelvic tilt is easy enough to recognize. There are two telltale signs:

● Exaggerated lumbar curve

● Bulging abdomen, even if the person has low body fat

When it’s most pronounced, the waistline of the client’s shorts will be diagonal to the floor, with the front angled downward, rather than horizontal.

The tricky part: figuring out if anterior pelvic tilt is a problem you need to address in your client’s training program. Like every other human trait, it exists on a continuum. Some people are just born with a pelvis that naturally tips forward and a butt that sticks out.

But for others, anterior pelvic tilt is a dysfunction that’s both caused by existing dysfunctions and a risk factor for new ones.

The clear indicators of problematic anterior pelvic tilt are quadriceps and low-back dominance, trouble activating the glutes, stiff and overactive hip flexors, and weak abdominal muscles.

Problematic APT can lead to poor exercise performance, particularly on movements like the squat and deadlift; low-back pain and injuries; and a higher risk of knee pain—all of which can, in turn, exacerbate the anterior pelvic tilt even more.

CONTENTS

· The science of anterior pelvic tilt

· Common causes of anterior pelvic tilt

· How to fix anterior pelvic tilt

Step 1: Master the lying pelvic tilt

Step 2: Progress to the standing pelvic tilt

Step 3: Perfect the hip hinge pattern

Step 4: Strengthen the muscles that promote posterior pelvic tilt

Step 5: Emphasize spinal alignment on deadlifts, squats, presses, and other compound lifts

· Squeezing the glutes and posteriorly tilting the pelvis during the rest of the workout

· FAQ

1. What muscles are weak in anterior pelvic tilt?

2. Does anterior pelvic tilt cause tight hamstrings?

3. Does anterior pelvic tilt cause back pain?

4. How long does it take to fix anterior pelvic tilt?

The science of anterior pelvic tilt

What we call a “neutral” pelvis is actually tilted forward slightly—less than 5 degrees for men and 10 degrees for women. That leaves you with a small lordotic curve. A perfectly flat lumbar spine results in posterior pelvic tilt, which can be just as dysfunctional as anterior tilt.

Short, stiff hip flexors are the central feature of anterior pelvic tilt. The iliacus, psoas, and rectus femoris may be naturally tight, or they could become that way as an adaptation to your training or lifestyle. (More of that in a moment.) Either way, they pull your pelvis forward, which lengthens and weakens your hamstrings.

This muscle imbalance involves reciprocal inhibition, a process in which muscles on one side of a joint have to relax so they can accommodate muscle contraction on the other side.

The same thing happens in the lumbar area. When the spinal erectors are overactive, they exaggerate the lumbar curve. That, in turn, lengthens and weakens your abdominal muscles, resulting in a stomach bulge that none of your clients want.

Common causes of anterior pelvic tilt

Women naturally have more anterior tilt than men, and are also more likely to develop excessive anterior pelvic tilt. These are the usual suspects:

Sedentary lifestyle

Prolonged sitting means the hip flexors spend the majority of the day in a shortened position. The glutes are inactive (not much they can do when you’re sitting on them) while the spinal extensors fire continually to keep your torso upright.

Movement and activity patterns

Picture a client who works out regularly, but also has a job that keeps her chained to a desk much of the day, combined with a lengthy commute.

All the problems created by sitting affect how she does common exercises in the gym. If the glutes and hamstrings don’t fire properly, the lumbar extensors can take too large a role during squats and hip extension. Same with overhead presses: The spinal erectors can pull the torso into a swayback posture. The movement feels “correct” to the client, but over time and with heavier loads, she can end up with back, knee, or hamstring injuries.

How to fix anterior pelvic tilt

I’ve coached a lot of clients with anterior pelvic tilt, and in my experience, strength training is the most effective way to change lumbopelvic posture. The following protocol is one I’ve developed through a lot of trial and error. (There’s only so much you can learn from reading science and theory on the subject.)

But before I show the exercises, I want to mention what doesn’t work. Typically, hip flexor stretches are considered a primary tool to alleviate anterior pelvic tilt. And it seems to make sense. If the problem is short and stiff hip flexors, why wouldn’t you stretch them?

Two reasons:

1. Stretching those muscles doesn’t actually address the reason why they’re tight. It can even lead to more back pain, as Dean Somerset explains in this article.

2. The best way to address anterior pelvic tilt is to strengthen posterior tilt, the opposite movement pattern.

READ ALSO: 15 Common Mobility Mistakes

Step 1: Master the lying pelvic tilt

Clients who have the hallmarks of excessive anterior pelvic tilt—bulging abdomen, back pain, poor glute strength, difficulty mastering the squat movement pattern—often have no idea how to posteriorly tilt their pelvis. Learning that movement is the first step in my program.

The lying pelvic tilt is a great way to do it, since “push your lower back into the ground” is an easy cue for most people to understand and perform.

Step 2: Progress to the standing pelvic tilt

“Squeeze the glutes” is an excellent cue for the standing pelvic tilt, as contracting the glutes will make the posterior tilt feel more natural.

Step 3: Perfect the hip hinge pattern

The pull-through is one of the most effective exercises I’ve used to teach clients the hip hinge pattern.

Superficially, it resembles the deadlift, kettlebell swing, and other hip-dominant exercises. But there’s one key difference: Because the source of resistance is behind the client, he’s forced to shift his weight backwards.

I typically use three cues:

1. “Chest high” at the beginning and end

2. “Push the hips back” in the middle

3. “Squeeze the glutes” at the finish

The cue I won’t use is “arch your back,” which I’ll discuss in more detail in a moment.

Step 4: Strengthen the muscles that promote posterior pelvic tilt

Every day, in every crowded gym, you can find someone doing planks with excessive anterior pelvic tilt, which can only make the problem worse.

As you can see in the picture below, the RKC plank achieves posterior tilt with simultaneous contraction of the core and gluteus maximus, combined with tension in the legs and shoulder girdle. (If you’re not familiar with the exercise, check out this detailed description by John Rusin, DPT.)

Step 5: Emphasize spinal alignment on deadlifts, squats, presses, and other compound lifts

With most clients, “arch your back” is a useful cue for deadlifts and other hip-dominant exercises. Same with exercises in which clients are likely to round their backs, like box squats.

But telling someone with anterior pelvic tilt to arch can do more harm than good. The lumbar curve is already exaggerated, especially on deadlifts, when someone with APT might arch his back throughout the entire lift. That increases the risk for spinal damage.

And the deadlift is just one problematic exercise for a client with anterior pelvic tilt. You may see swayback on overhead presses and pulldowns. A quad-dominant client with poor glute activation could struggle with squats, and her poor technique could set her up for injuries.

READ ALSO: How to Fix “Butt Wink” in the Squat

On both squats and deadlifts, the two cues that work best for me are “spread the floor apart”—that is, push against the outside of the feet—and “drive through your heels.” You also want to assess the client’s technique with a side view, paying close attention to the bar’s trajectory. It should travel in a vertical line over the midfoot, with the spine in neutral alignment.

Neck and head position are typically less important. Telling a client to tuck his chin is a “safe” tip, in that it can help maintain a neutral neck position. But to be honest, I’ve found it doesn’t really matter as much as we think it should. As long as the client isn’t looking up at the ceiling, or off to the side, it’s far more important to focus on spinal alignment.

What about sets and reps?

You almost always want to use fewer reps on complex movements like squats and deadlifts, and that’s especially true for clients with anterior pelvic tilt. The fewer reps the client does, the less chance there is for technique to break down.

The RKC plank in particular works best with lower volume and higher effort. You’re asking a client to posteriorly tilt his pelvis by contracting his abs and glutes, and also generate high levels of tension in the upper back, chest, and thighs. Holding that position for 10 seconds can feel like an eternity.

That’s why you’ll get the best results with two to four holds, resting at least 30 seconds in between.

As for total workout volume, it really depends on the client. You don’t want to chase fatigue on any movement in which spinal alignment is challenged. But if you program these exercises early in the workout, you can finish with less technically complex movements that create the appropriate training effect.

Squeezing the glutes and posteriorly tilting the pelvis during the rest of the workout

While it’s not a requirement, posteriorly tilting the pelvis during other types of exercises stabilizes the spine and even gives you some static glute training. Consider cueing a client with anterior pelvic tilt to squeeze the glutes while doing presses, push-ups, pulldowns, and biceps and triceps exercises.

It’s also helpful to remind the client to squeeze her glutes as she finishes hip-dominant exercises like deadlifts, hip thrusts, and box squats.

FAQ

1. What muscles are weak in anterior pelvic tilt?

It could be any of them, or all of them. Or muscle strength may not be the issue at all.

As noted at the beginning of the article, someone with anterior pelvic tilt always has short, stiff hip flexors. And if those muscles are short and tight enough to pull the pelvis forward, that means the hamstrings have to be compromised in some way. They’re longer and usually weaker than they should be. Same with the abdominals. And the glutes are usually weak as well.

But someone could also be strong in most or all of those muscles, and that person’s APT could be genetic or the result of how she uses her muscles. In particular, athletes who need strength, power, and speed develop APT. It might even be a beneficial adaptation if shorter, stiffer hip flexors and longer hamstrings help them run faster or jump higher.

Something similar happens with lifters. As Bret Contreras explains here, APT can help someone generate more force at the start of a deadlift by putting more tension on the hamstrings. But it can also be a way to use the spinal erectors to make up for weak glutes during hip extension.

In all cases, you need to address your clients’ movement patterns as much as the muscles used in the movements.

2. Does anterior pelvic tilt cause tight hamstrings?

Possibly. Muscles that are chronically lengthened will tend to be tight, whether they’re strong or weak. If a muscle is already stretched, it’s going to reach maximum tension sooner than a muscle without that handicap.

But here’s a riddle: If the hamstrings are tight, why don’t they pull the pelvis down into a neutral position?

The answer, as Mike Reinold explains here, is that the hamstrings may be fine. But because APT shifts the top of the pelvis forward, and the hamstrings are attached to the bottom of the pelvis, they have to start any movement from a suboptimal position, even if they’re capable of an optimal range of motion.

Again, this all happens in degrees.

3. Does anterior pelvic tilt cause back pain?

There doesn’t seem to be any direct cause-and-effect relationship between anterior tilt and low back pain. “I don’t give it much thought if I see someone standing or walking around with it,” says physical therapist Chad Waterbury, DPT. “However, APT can definitely be a problem if a person does rotational sports.”

Take the example of a golfer who has low back pain. “The first thing I’ll say is, ‘Show me your 5-iron posture.’” If the golfer sets up for a shot with severe anterior pelvic tilt, Waterbury says his first goal is to get his pelvis to neutral.

Swinging a bat, club, or racquet with APT is one of two related problems for rotational athletes. The other is thoracic rotation. “Most people lack optimal thoracic rotation—45 degrees of rotation in each direction while seated with hands behind the head—whether they have APT or not,” Waterbury says. They’ll compensate for that missing range of motion by moving something else, usually the lumbar spine. That’s a textbook condition for low back pain.

Fortunately, both problems can be addressed: Shift the pelvis into a neutral position before swinging (you'll find a detailed explanation here), and work on thoracic rotation with drills like these.

READ ALSO: How to Train Clients Who Have Back Pain

4. How long does it take to fix anterior pelvic tilt?

It’s impossible to say. If it’s a genetic trait, you may not be able to make a permanent change.

But you can fix movement patterns. The more you focus on changing the way you sit, the way you stand, and the way you do key exercises, the faster and more permanently you can change the effects of anterior pelvic tilt.

Thus, while the anatomical change may be minimal, you can keep it from becoming dysfunctional and minimize the risk of injury.

Final thoughts

As a final note, I want to emphasize the range of alignments that humans can display without creating dysfunction. Even if you recognize the universal characteristics of anterior pelvic tilt in a client, be sure to assess flexibility, strength, and movement quality before embarking on a program to address it.