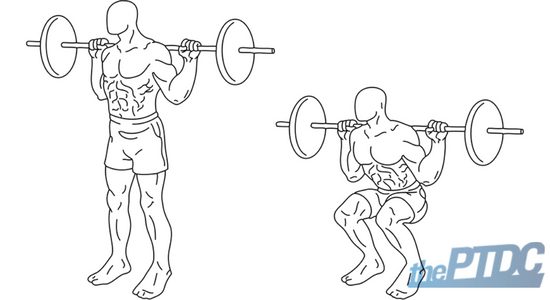

When programming for clients, there are certain "non-negotiable" exercises that make up the foundation of human movement, athletic development, and quality training.

The humble squat is one of those foundational and essential movements. More than likely, you want to include squats in your client's program, but there's more to it than meets the eye.

Squatting is an essential human movement that every individual has done, will do, and will continue to do throughout life.

Can your client get up? Can he get down? Is he getting up and down safely?

Safety and joint longevity are important considerations. When it comes to programming a squat, you need to understand the squat's appropriate progressions, regressions, and modifications for that individual to succeed without incurring avoidable injuries. Don't worry, we'll go into it all.

Let's first discuss why the squat is a critical exercise in your client's training program and how it'll impact his or her life. Then we'll look at some progressions, regressions, or modifications for safe and effective squatting.

Why your clients should buy into the squatting hype

The reason we squat goes deeper than just hammering out heavy doubles for a workout. Without essential techniques, it's not possible to fully experience and interact with the world in the way we were designed to.

The squat pattern is how a child transitions from the six-point crawling position to standing upright, and eventually walking. Similarly, the squat pattern is how that toddler's parents are able to crouch low enough and then scoop their child up. More importantly still, the squat will be important for a grandmother or grandfather to get in and out of the seated position to, perhaps, play with their grandkids.

Chances are, your clients aren't going to care for Olympic 100s or bodybuilding trophies. They care about their ability to climb stairs without pain, play sports for fun, and live a healthier life. The benefits of squats transfer to other aspects in your client's everyday life, too, most notably running speed and general athleticism.

Sometimes, however, clients don't immediately buy into squatting. They may think it'll be bad for them. When explaining squats to a first-time client, it's important to explain to him or her that squatting is a movement pattern that is deeply ingrained in their everyday life, whether they know it or not.

Your talking points should evolve and adapt to each client's unique needs and concerns. Emphasize activities, such as walking, climbing stairs, getting out of bed, and bending over to tie their shoes, to paint a more vivid picture of the many benefits that squats could provide them. Some clients would appreciate how squatting burns a lot of calories while they're doing them, and even when they're not doing them.

Every client presents a different case, and a great trainer's knowledge must be versatile enough to adapt to each. Those are the things that are important to the client. As the trainer, there are important things that you should take note of, too. More specifically, you should familiarize yourself with the anatomy and physiology behind the squat.

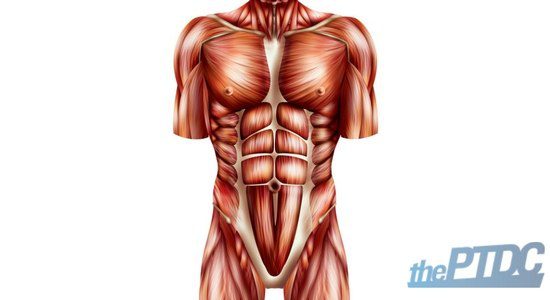

Learning the functional anatomy of the bodyweight squat

Before we begin, it's worth noting that we are examining the squat as it exists as a sagittal plane exercise. Variations that incorporate frontal or transverse movement are not being considered. Moreover, the form discussed is for a standard bodyweight squat, or a lightweight goblet or back squat. Furthermore, we will not be examining the squat variations among powerlifting, bodybuilding, and CrossFit.

With that out of the way, observe this Jean Fernel quote:

"Anatomy is to physiology as geography is to history; it describes the theatre of events."

As Fernel waxes poetic in her quote, anatomy is simply the place where events happen. Many "events" within your body come together during a squat: the structures of the skeletal systems are driven by forces which are generated by your neuro, fascial, and muscular systems. These, in turn, are further fueled by your cardiorespiratory, endocrine, and metabolic pathways.

All the muscles involved when you start from the bottom.

All force starts and ends with the ground in a squat. It is the constant in a system that presents much change. When looking at the anatomy of the squat, you need to study the foot, ankle, and tibia just as critically as we study the hip, thigh, and core.

When a client squats, observe what's happening in the following:

- The space from midfoot to heel, or calcaneus, serves as the optimal point of force generation, as the lifter drives through the ground.

- This "driving" action causes the ankle to dorsiflex, which recruits the tibialis anterior, the muscle on the front of the tibia, to fire and create toe-to-knee flexion.

- The calf muscles, the gastrocnemius and soleus, function to assist the tibialis anterior by keeping the heel, ankle, and knee stabilized as the tibia tilts forward to accommodate the descending femur, hip, and upper body.

As a result, the knee joint--where the tibia, fibula, and femur merge--functions under compressive and shearing forces during the squat. Put simply, shearing force is a lateral and medial pull out of the line of force. Meanwhile, compressive force is a vertical force that causes something to be squeezed or compressed.

Ultimately, it's in everyone's best interest to minimize shearing forces, while also managing compressive forces with proper loading of the hips.

Proper loading of the hips, in this case, involves recruiting the hamstrings, quadriceps, glutes, abductors, and even the adductor magnus to be force generators. Each of these muscles play a key role in performing the squat.

The hamstrings--also called semimembranous, semitendonous, and biceps femoris-function concentrically as the hips draw toward the floor. Think of a leg curl, in which the exercise brings the heel to the butt. In a similar fashion, the squat brings the butt to the heels, although full "ass-to-grass" squats are not appropriate for everyone (which we will discuss later).

As the hamstrings contract, they store energy, or elasticity, to power the upward drive from the bottom position of a squat and to assist the glutes and quadriceps.

The quadriceps-the rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis-function concentrically during the upward phase of the squat. In effect, the quadriceps are what finish a squat. The eccentric phase serves to stabilize the knee and hip joints during the downward motion, as well as storing energy for the upward drive.

The gluteus maximus, minimus, medius, and adductor magnus all serve as hip extensors during the squat. From the bottom to the top, they function as force generators to complete the repetition. They are loaded during the descent with a controlled lengthening of the muscle tissue, which allows for a powerful amortization phase (see below) of the squat.

The amortization phase is quite simply the period of time during which no motion occurs between the eccentric and concentric contractions of any given movement. This phase is especially critical during a squat since the majority of failed attempts will occur at this point.

Other muscles, such as the adductor brevis and longus, tensor fascia latae, sartorious, piriformis, and iliacus, stabilize the hips and knee joints during the entire movement. This allows for the major movers to utilize full force to create movement.

The core's role in the squat.

The abdominal wall--your client's core--is critical to a high-functioning squat.

As the pelvis rotates into an anterior tilt, it is the contraction of the transverse abdominals, external and internal obliques, and spinal erectors that keep the torso upright and in proper position. All of these aforementioned muscles, along with the rectus abdominus, psoas complex, serratus, and even latissimus dorsi, are critical in stabilizing the upper body above a rotating hip joint.

Here coaches may typically teach their clients to draw in a full breath into their stomach, where the abdominal wall is drawn tight. This is done to stabilize the spine internally and better brace the core to resist flexion. The breathing doesn't need to be overly complex at this juncture. In fact, most individuals will naturally hold their breathe when they exert themselves. Additionally, such a breathing technique would impact systolic blood pressure and is not suitable for all clients, specifically those who suffer from a hernia or high blood pressure, for example.

A simple cue to help clients learn to breathe 'correctly' is to tell them to take a breath like they are about to plunge their head underwater, and to brace their core as though they were about to be hit in the stomach. It's important to teach clients to remain tense throughout the eccentric phase of the squat and exhale smoothly but forcefully during the concentric phase.

How to assess your client's squat

You must be capable of programming many variations of the squat, as every client will present a different set of goals, abilities, and even dysfunctions that can greatly impact his starting point, as well as his finish line.

Don't just assume.

In order to adequately train the squat pattern, you need to be able to see your clients move; hear your clients speak about their goals; and visualize what dysfunctions may arise as they describe their injury history, medical conditions, and overall fitness experience. This is typically through a physical assessment or screen, which provides a lot of quality data to guide your decisions.

Ask about your client's medical history, but wade carefully.

The assessment all starts with an initial conversation about that client's history. You can do this during an initial training consultation.

Obtaining medical information is important--both legally and ethically. A great trainer not only understands that they are mandated to document it appropriately, but also cares about the client's past.

Many clients may present a relatively clean bill of health: a little strain here, a pull there, and maybe even some surgery during their teenage years. Your clients may present multiple injuries, dysfunctions, and scars upon further probing. There seem to be no medical conditions that hinder them, and all of their day-of vitals (blood pressure, resting heart rate, and so on) are on point. It can be tempting to take these clients right into their workouts, but the problems may not be obvious.

For example, you may get a young 20-something who "just wants to be big", but has terrible valgus collapse, underactive glutes, and poor ankle mobility. Or a hypermobile girl who wants to develop her legs and backside, but lacks the stability necessary to squat safely under any external load. Or maybe the client has done surgery and physical therapy, gained a lot of weight from the inactivity, and might have the red flags that indicate a metabolic disorder.

This last group should be referred out to a specialist, or at least a discussion with their current therapist, in order to completely comprehend the problems and understand how to train the client safely and effectively. Anything outside your scope of practice should never be messed with from a legal and ethical standpoint.

Assessing at the onset of training will quickly identify the tightness in some areas, the lack of strength in others, and the individual's overall ability to squat.

Things to look for when assessing the client's squat

After the conversation about medical history and training goals, you can perform the Functional Movement Screen, or FMS. Created by Gray Cook and Mike Boyle, it is the gold standard method to assess the movement patterns of a client.

Everything from the deep squat to the push-up test provides critical information that will greatly impact the movements that can be, and should be, trained. Moreover, you'll glean data about movements that require specific attention prior to adding them into a program.

When assessing your clients, keep these questions in mind:

- How does the client stand? Do they favor one leg? Do they have rounded (internally rotated) shoulders?

The beginning of their squat should look exactly like their normal standing posture. It may worsen at the bottom of a squat (with or without load). Identifying discrepancies in leg length, hip mobility, or thoracic kyphosis is critical to setting a client up for success.

- How does the client walk? Do they have a limp? Do they turn out their toes excessively? Do they move at the ankle? Does their core rotate too much during foot strike?

Observe how they walk. A limp could reveal an injury that never quite healed. An externally rotated foot could point toward hip issues. If they have stiff ankles, they will struggle to "compress" into the depth of the squat, just as an over rotation of the core will cause stress to move into the sacral joints of the spine due to weak obliques.

- How does the client sit? Do they cross their legs immediately? Do they collapse into "keyboard" posture? Do they sit straight up and down and rigid?

People spend too much time sitting, and ironically, have gotten really good at being really bad at it. Does the kyphosis from their standing position get worse, or are they able to lift their ribs from their hips and elongate their core? The strength of their core is on display here. The other point here is, crossed legs aren't necessarily a bad thing, but most individuals cross the same leg on top. That means there may be uneven hip mobility between the two joints.

If the FMS is not an option, you can still gain a lot of information from doing the following the three exercises below. Note that throughout these assessment exercises, your role is to simply observe. After all, any assessment should be done with minimal cueing, as you want to learn the client's true baseline.

- High-Knee March

The high-knee march displays the tracking behavior of your client's hip, knee, and ankle. Additionally, it shows whether the client possesses adequate ability to remain upright during the squat.

A proficient and stable client should stay tall and upright throughout the march. Specifically:

- Their femurs (hip to knee) will track straight up and straight down with every foot strike. There will be no internal or external rotation at the hip, and the knee will drive to 90 degrees (or just above 90) at the top of the leg swing.

- The lower leg should remain strictly vertical regardless of the angle of the knee (bent or straight).

- The ankles should point the toes upwards, or dorsiflex, as the knee nears the chest. The ankles should point down, or plantar flex, as the foot strike goes into the ground and the leg rises again.

An unstable client will present many deviations from the aforementioned form.

- There may be spinal flexion as the client struggles to keep his core tight and his spine long. This is indicative of his ability to maintain core tension during complex movement, which is likely systemic of a weak anterior core, but could also point to a lack of neural connection.

- The knee may track medially or laterally across his body as he works to perform the knee drive. This will indicate weakness in the glutes and abductor or adductor complexes of the hips (usually abductor). Some individuals have weak hip muscles and poor neural connection, so their performance will vary from repetition to repetition.

- The lower leg may "kick" forward at the top of the knee drive. It may also "fall" inwards or outwards as a result of excessive joint laxity at the knee due to injury, athletic history (most common with dancers and gymnastics); or it could be a sign of hypermobility, a condition that makes all joints in the body "loose".

- The ankles may roll inwards or outwards at both foot strike and knee drive. The client may not be able to adequately dorsiflex their feet, even at the top of the knee drive; and thus, present plantar flexed feet at all times. This will lead to them "spiking" the floor and adding unneeded shock to the ankles and feet.

- Bodyweight squat

One of the best ways to see if clients can squat safely is to just ask them to squat.

Before letting them squat down, make sure they are in a space with enough room to stumble in any direction, if needed. And of course, avoid adding any external load. If there is any recent injury history, or the client is particularly concerned about performing the movement, it may be best to ensure a stable structure is nearby for him to use as support.

Remember, while your client squats down on his or her own, it is best for you to refrain from coaching cues to allow your clients to perform the squat pattern as they know it. . Observe from the ground up to best assess the squat pattern. This will ultimately lead to a faster progression because discrepancies and dysfunctions will not be masked by quality coaching.

When watching a client squat, you should be keeping the following check list of questions top of mind:

- How does the client set up their feet? Are they so narrow that their femurs are forced to shoot out in front of the toes, thus causing a weight shift into the knees and toes? Or, does the client set up wide and externally rotate so that they don't have to push their hips back or travel as far in the squat?

- Does the client have action at the ankles? Do they actively dorsiflex and press through the heels of their foot as they squat? Or, do they push off the toes and plantar flex?

- Do the knees track too far forward? Is it a result of the feet? Look at the hip --is there adequate hip flexion? The knees over toes isn't always right, but it does give a guide as to where the stress of the squat is going.

- Do the knees collapse inwards? Do they rotate too far outwards? Are they able to keep them in line during the downward phase, but lose control as they change directions during the amortization phase?

- Do the hips extend or just drop? Do they tilt their pelvis at all?

- Does the core look rigid and upright? Is the spine rounding as they get to the bottom? Are they overarching their lumbar spine to keep their chest upright?

- Where do they like to place their hands? Do they push them out in front like a zombie, hold them on their head, simulate a barbell squat, or go fist in hand?

- Where do they look? Do they bend at the cervical spine?

As the client completes his squat, you should have a checklist of action items that need attention. Some muscles may need strengthening while others need flexibility. One joint may need more mobility while another requires stability.

This checklist will allow you to scan the squat in an orderly fashion and discover the sources of problems. Always know that a problem further up the body should be referenced to the joint below it before diagnosing it as the issue.

- Plank

The purpose of a plank assessment is simple: Can a client maintain a tight core for 30 to 60 seconds?

When coaching the plank, keep these things in mind:

- Set your client up in a tight plank position either on forearms or hands. The position will be based upon what the client is comfortable doing and not forced by the coach. Tension can be created throughout either position if the following steps are adhered to.

- Feet should be tight together as though they are holding something between their shoes. (Cue: Hold a playing card between your shoes.)

- Hands will be separated. Both will make a fist. The shoulders are flared outwards and the hips are tilted up slightly to ensure the back is perfectly flat. (Cue: Pull the floor apart beneath you.)

- Glutes contract as the client draws their belly button into their back. (Cue: Squeeze your glutes like you are holding a credit card in between your cheeks.)

Ideally, your client will be able to maintain rigidity, or something close to it, for the time allotted. If your client struggles to hold longer than a few seconds, it could be a sign of a weak transverse abdominus, lower back pain, or an inability to exert against tension. All of these factors would contraindicate a loaded squat pattern during the initial phase of that client's program.

Skeletal considerations in a squat pattern

- A mild arch in the lumbar spine is acceptable during a squat pattern, but too much is a risk. Thoracic kyphosis, or rounding of the upper back, must be avoided, especially under load. "Tall spine and broad chest like you are getting your picture taken" is an image that can help clients visualize what needs to be executed.

- Coach a neutral cervical spine. The head should remain at the same angle as the rest of the spine, which means no looking up or looking down during the pattern. "Look fifty feet in front of you" is a cue that will help this.

- The knees should abduct to no further than the angle created by the toes. External rotation at the hip should be no more than 30 degrees in the majority of individuals who squat with or without weight.

The assessment provides an opportunity to see what a client presents when tasked with "bits" of the squat, as well as a simple squat itself. These three moves expose weaknesses while simultaneously highlighting strengths. For example, if your client were an avid cyclist, he would have tremendous force capability with his legs and above-average mobility through the hips. However, he presents a weaker anterior core as a result of bending over the bars of the bike. These revelations will dictate which squat variations would be safe for him to execute immediately, as well as point toward important accessory exercises that will address weak points.

Wrapping it all together

The squat is more than just a great way to build muscles on your thighs, accentuate your glutes, or bang around more plates than a late night diner. It is essential to being human.

As a trainer, we should understand a squat is important and complex. It is just as important to assess your client's preparedness for a squat and their reasoning behind wanting to learn or perform it. Regressed or progressed, accessory or primary, the squat has a place in all programs.

Learn to coach the squat like a boss:

- 5 Steps to Dealing With Anterior Pelvic Tilt by Eirik Garnas

- The Real Reason Why People Must Squat Differently by Ryan DeBell

- What's Your Optimal Squat Stance? by Dean Somerset