- Trainers can "create" clients by building their capacity to train, even with back pain.

- A thorough assessment will identify the cause of pain, such as offending motions, postures, loads, and other variables that would be familiar to the trainer.

- Avoiding clients' pain triggers will allow a desensitization of the pain pathway.

- Trainers can build a foundation for pain-free movement once the pain triggers have been removed.

- It is important to know when to progress and regress a client.

- Trainers have the potential to play the largest role in influencing movement patterns that will either cause or cure most back pain.

When patients with back pain are referred to me, most show symptoms that have been caused by trainers and clinicians. At the same time, I will state that you, as the trainer, can be the most effective professional in reducing lower back pain. Indeed, your role in your client's spinal health cannot be overemphasized. The following is an overview that aims to empower you and your clients to reduce pain and encourage the joy that comes from disciplined and competent, pain-free movement.

There is no such thing as non-specific back pain. There is always a cause. In nearly all cases, the pain is worsened and may also be relieved by specific motions, postures, and loads. Trainers who work within this reality can create able-bodied, robust clients.

Regrettably, our medical system is woefully inadequate for dealing with back pain. Most patients rarely receive the most important part of the prescription for getting rid of back pain from their doctor. That is, the required knowledge and understanding of their condition that would allow them to become their own best advocate.

Instead, they might receive a 10- or 15-minute appointment, which is simply not sufficient to diagnose back pain in the first place. By the end, they are left frustrated and clueless about what behaviors they must stop to address the cause of their pain. Worse, they have no idea as to what is required to build a foundation for pain-free movement.

"Passive" treatments like prescriptions for pain medication or ultrasound may be a part of a broader approach, but without a plan to stop the cause itself, these rarely create a long-term solution. What's needed is a thorough assessment of an individual's specific pain triggers. This will identify a pain mechanism that will, in turn, guide a targeted treatment plan. The exam to find a client's pain triggers is not difficult, and I will coach you through the process shortly.

Before we get to that, understand that there are several popular myths about back pain that can thwart recovery if neither the patient nor trainer is clear about their objectives toward moving without pain.

Terms such as "non-specific back pain", "ideopathic back pain", and "lumbosacral strain" are often used to label patients with back pain. In actuality, these labels simply indicate that the patient has not had a competent assessment of the mechanism for their pain, and thus, have a very "non-specific diagnosis."

Another popular diagnosis is "degenerative disc disease." This kind of diagnosis is the equivalent of telling your mother-in-law with wrinkles that she has "degenerative face disease!" I get so disheartened when a distraught patient expresses his fears to me about this supposedly progressive disease; and then when I tell him that he actually has no such disease, the reaction varies from relief to anger toward the person who mislabeled his condition.

Thankfully, trainers and clinicians can help guide patients through a more thorough self-assessment that will reveal their precise pain triggers. This approach often introduces patients to the first accurate assessment of their unique causes of pain.

Additionally, by treating patients with back pain as individuals, trainers and clinicians would be able to better understand why one approach may be more effective at removing pain from one patient but may end up hurting another. Using the knowledge gained from their assessment, they can:

- Remove the pain triggers.

- Create the foundation for pain-free movement.

The overarching goals here are to identify and follow an approach that will be effective for patients and their unique causes of discomfort.

The Assessment

It is possible but difficult to try to diagnose painful back disorders based on anatomical structure alone. A surgeon may be able to perform a tissue-based diagnosis by looking at X-rays and scans and by "poking around," but they stand to benefit mainly by "cutting the pain out."

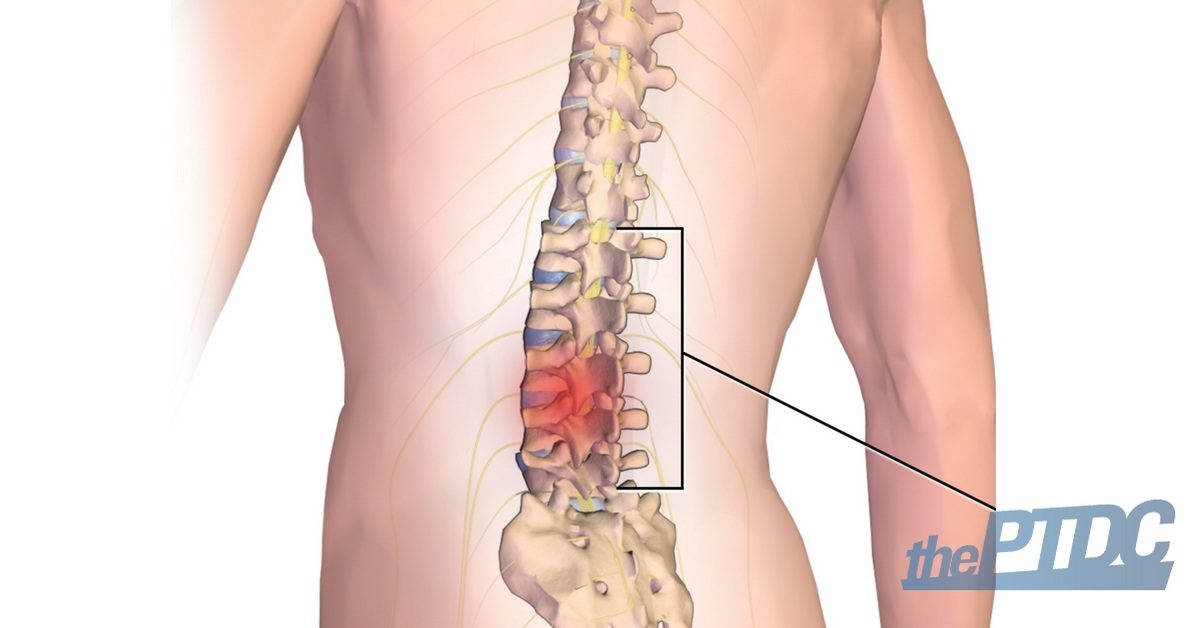

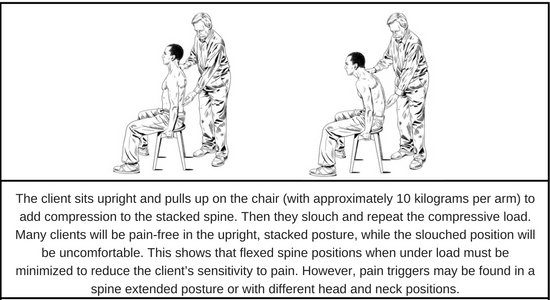

Having studied a large body of the literature, I can tell you that the mechanism of back pain is almost always exacerbated by a particular motion, posture, or load. A series of simple diagnostic tests will serve to identify the motions, postures, or loads that can both worsen a client's back pain and be well tolerated by the client. Here is an example of an assessment that will reveal if posture and spine curvature affect the client's pain:

Many other tests look at whether head position changes pain sensitivity, or whether certain hip movements or even movements like lunges cause or take the pain away. Shear testing, for example, shows which clients are qualified to perform a kettlebell swing and which should avoid them. For more, you can check one of my books Low Back Disorders-3rd Edition With Web Resource: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation

By following this system, you will identify clients with extension intolerance, shear load intolerance, and many others, and categorize them based on their intolerances. For example, workers with "spine flexion bending intolerance" will probably be exacerbated by sitting, tying shoes, and any similar motions that cause the spine to bend; yet they will tend to have a very high load tolerance when the motion is instead transferred to their hip joints.

With your inventory of your client's precise triggers as your guide, you can create a prevention plan to eliminate these specific pain triggers. The goal of the complete rehabilitation plan, then, is to enhance function while avoiding these triggers. More importantly, you've given your client guidance on how they can avoid their own pain triggers.

Essential Elements of Function

Certain loads on the spine are necessary and actually part of maintaining a healthy back, but some are harmful and can accumulate damage in the spine over time. For example, bending a thin branch back and forth causes no damage while bending a thick branch would cause it to break. Thicker tubes simply build more stress and break sooner. Thicker spines in large people follow the same principle, and so, an astute trainer should consider this in the programming. Thus, every client is different in his or her reaction to loading, which is governed by biology, injury or training adaptation, genetics, and rate of repair. The good news is that one can achieve a healthy, pain-free back with the optimal amount of load--not too much or too little.

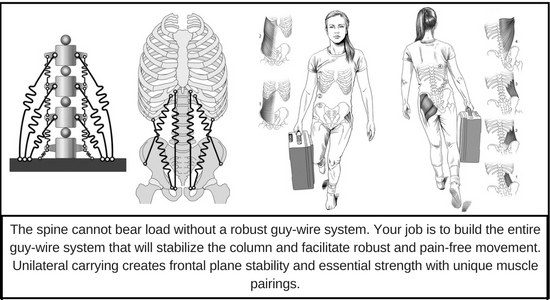

Not surprisingly, proper muscle function is important to supporting a robust and pain-free back. Without the surrounding muscles, the spine would be rendered totally useless and incapable of supporting the weight of the upper body. Quite simply, it would buckle. We have seen this in people with insufficient muscle coordination. Muscles must contract in a coordinated manner that allows them to act similarly to guy-wires, which are high-tension cables that reinforce a structure's stability, and prevent the spine from buckling under a high load. By stiffening and stabilizing the torso, these muscles allow movement to be propelled through the arms and legs, but this stress-free movement is possible only when it is combined with corresponding mobility at the shoulders and hips.

People often wonder whether stiffness or mobility should be valued more when it comes to using the core to manage the human spine. It turns out that both are needed. Your spine muscles are constantly tuning this interplay between stability and mobility, much like how some parts in an automobile stiffen and others create motion to enable it to perform what it needs to. This "sweet spot" is governed by a set of movement principles.

Take a backhoe, for example, which must place legs on the ground to stabilize and allow the articulated link to dig. The articulated link of the human body requires proximal stability (core) to enable effective distal mobility and power flow to distal links (arms and legs distal to the shoulders and hips). Another example: consider the spine as a flexible rod. Without any stiffness, the upright rod will buckle when load is placed at the top. If you apply guy-wires around the rod, the stiffness will allow the rod to bear high load. In the spine, bracing torso muscle activity is essential for people to enhance their lifting ability without risk of triggering pain.

What Causes Back Disorders?

While there are many causes of back disorders, the scientific literature is strongest for several possible mechanical causes.

Once the patient has experienced pain, and the nerve system is sensitized, the way the person reacts to the pain is modulated by a host of variables that can increase or decrease the pain sensitivity. Biology, adaptation, size of the person, and previous injury history all influence the patient's reaction to load magnitude, repetition, and duration. For example, the spinal discs have a fatigue life, or essentially, a limited number of bending motions the patient can withstand before they become painful.

Pain sensitivity, from moving the spine and its bending discs, is modulated by hydration, among other variables. For example, discs are more hydrated and stressed after rising from bed, making bending type exercises at this time more problematic. Other variables include the corresponding load at the time of the bending motion, the direction of the bending axis, and a patient's routine and approach to training. If an individual continues to bend a pain-sensitive disc from continuing to do a flexion-stretch on his back, he will most likely experience worse symptoms or at least an aggravated (and recurring) situation. The same mechanism is exacerbated by extended periods of sitting, when the spine (particularly the lowest lumbar discs) is bent forward in flexion.

These flexion-intolerant patients are sometimes told to pull their knees to their chest to obtain relief. This motion activates the stretch receptors in the back extensor muscles and offers pain relief for about 15 minutes, but unbeknownst to the patient, this bending has actually caused further damage to and/or sensitization of the underlying pain mechanism. In other words, when patients may have found a "quick fix", or short-term cure, they are actually sensitizing their pain trigger and inviting additional pain attacks in the future. These types of stretches initiate a dangerous cycle: they may temporarily numb pain, but do very little to address the pain in the long-term.

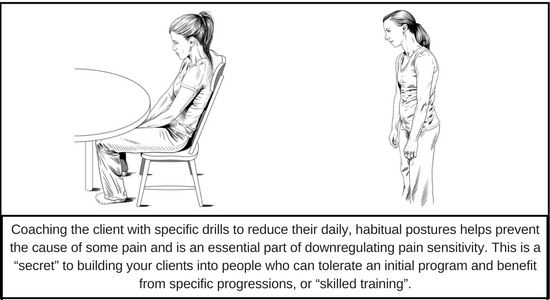

Oftentimes, these types of patients find relief through frequent postural changes and even fast walking, but they cannot tolerate sitting. In these cases, the patient should use a small cushion to assist with lumbar support to prevent the lumbar flexion trigger while sitting. Additionally, special exercises designed to combat the cumulative stresses from sitting are also usually helpful. For example, encoding a hip hinge movement pattern to replace their spine-bending pattern is an important first objective for the trainer. Of course, specific strategies to avoid the cause and create a pain-free foundation will differ between different sub-categories. That is just one example where provocative testing and classification of the back pain sufferer results in better prevention and rehabilitation approaches than a classic, rushed doctor's appointment.

Consider the specific movements used by athletes, construction workers, farmers, and many other active populations. By first appropriately identifying a set of specific stressors, all of these individuals are able to modify their movements in order to eliminate the pain triggers and perform their required work in a way that spares their spine. As with any other type of pain, the more the triggers themselves are avoided, the faster the sufferer will be able to desensitize their reaction to them altogether. By following a few rules for back health and function, it is possible for you to design a plan to build resilience to pain triggers.

What You Need to Know

When dealing with a client suffering from lower back pain, you should be familiar with:

Mechanisms of injury

Tissue damage has a specific cause. For example, spine disc bulges don't just happen. They are caused by a combination of repeated flexion bending while the spine is under load, such as someone squatting too deeply when they have stiffer hips. This is a good reminder that assessing the hips is essential for guiding exercise decisions. Another example is disc tears, which result from excessive twisting while under load. Exercises like twisting slosh pipes and Russian twists with a loaded med ball will enhance strength over the short term, but will create delamination in the disc annulus and eventually lead to tears where pain-free loading is no longer possible. Further, end plate fractures, schmorles nodes, and so on are from overloads of cumulative compression. This happens when trainers progress clients too quickly in exercises like deadlifts.

Identify the training goals

Every client should be able to answer the question, "What are your training goals?" Is it to reduce pain, enhance capacity for work or to have fun? Write these down then choose specific exercises to create the ability. Exercises that you prescribe are simply tools used to achieve this goal, whatever it may be.

Creating a program for health and a pain-free life is very different from creating for a specific athletic goal. For reducing pain, we follow the principles which we have created over the years to reduce injury mechanisms and enhance capacity. For enhancing athleticism, we document the specific demands of a particular sport and then assess the client for what they possess and don't possess. Then you train that which they lack or are weak in. This process is outlined in my book Ultimate Back Fitness and Performance.

How to assess a client

The old idea of measuring a client's range of motion will contribute little to your success with the client. Instead, understand his or her pain history, which will establish a starting baseline of existing weak points. Then pain provocation tests will reveal the specific pain triggers in terms of offending motions postures and loads. Together these will guide your selection of movement techniques to help your client.

Know how to coach and cue movement

Coaching cues include verbal cues which simply describe the desired movement; internal cues where the patient "feels" a specific muscle or movement pattern occurring; and external cues where the patient reacts to a sound or visual cue. Every client has their learning style. Some clients may respond more strongly to different types of cues. You should try different cues and observe which is most effective. An astute trainer becomes aware of the best cues for a particular client to achieve the desired pain-free movement.

How, what, and when to progress (or regress)

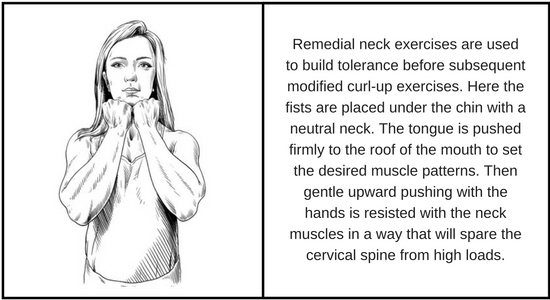

Generally, the rule of thumb is that the client must be able to perform an exercise without pain and with competent mechanics before a progression may occur. Failure to achieve this may require a regression. For example, a client who is unable to perform a curl-up because of neck pain may require some remedial cervical exercise.

When to refer on to another expert

There will be times when the situation is beyond the skill level or scope of the trainer. Obviously, it is best to refer out in those cases, but the question is: to whom should the referral be made? Good trainers should have a list of competent clinicians with whom they have built a solid relationship. In my own network, I have excellent mobilizers, expert trainers who coach movement flawlessly and create effective programs, outstanding physical medicine doctors who can assess the pain trigger pathology beyond movement triggers, therapists who address co-morbidities, and many other McGill providers around the world.

A Note on "Pain Science"

There is a trend on the internet with the opinion that it is detrimental to explain the pain trigger to a client, that it could create "movement fear." They suggest coaching the client to just continue moving. I have found that following this approach has actually created more movement fear, as the client remains clueless about what causes him pain or why he suffers from repeated acute bouts of pain. This is contrary to the neuroscience of pain.

Every time pain is triggered, central sensitization occurs. This is akin to hitting your thumb over and over with a hammer. Eventually, the thumb is so sensitized that the lightest of touches triggers pain--and fear. It's important to understand that the hammer itself is the cause and that it must be removed. Once it is, the pain sensitivity can be reduced so that pain-free movement slowly becomes possible over time. So the key is to remove the faulty movement pattern first, then use the pain-free ability to create a smarter movement strategy and exercise program.

In reality, any movement approach can induce fear. The key is in the coaching. Being able to explain the mechanism of pain so that the client understands he is in full control of his pain is very empowering for the client. This way the client begins to understand that moving in specific ways to avoid the triggers will eliminate them, and also alleviates the fear of never knowing when the next onset of pain could occur.

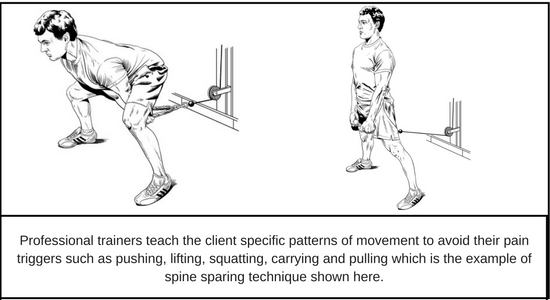

Coach your patient in the "movement tools" to avoid their specific triggers and you will improve confidence in their own movements, as well as allow them to increase the pain-free athleticism that they are paying you to create.

A Note on Trainer Professionalism

Excellent trainers take responsibility to increase skill in their craft. My colleagues and I were involved in a study, entitled Exercise-based performance enhancement and injury prevention for firefighters: Contrasting the fitness- and movement-related adaptations to two training methodologies. (J Strength Cond Res., 29(9):2441-59) that showed coaching professionalism matters.

In the study, we took the Pensacola fire department and created three training groups: one acted as a control group; the second trained by exercising for reps but didn't worry about fatigue compromising form; and the third group was coached by excellent trainers who insisted on good form. We measured firefighting skill and the ability to execute tasks in body-sparing ways.

The group that got more attentive coaching performed the firefighting tasks with more skill and less load on their bodies. The group that had gone without coaching saw no additional benefits in their ability from exercising. In fact, they actually performed the firefighting tasks with more injury mechanisms present in their movement. The results of this study show that your coaching efforts do matter. Keep cuing movements that avoid pain mechanisms, and you will create a client who can actually train with you. Failure to incorporate this professionalism will simply mean you will lose clients.

In summary, there is no such thing as "non-specific back pain" or degenerative disc disease. Rather, there are only those individuals who have not had a thorough assessment. There is, however, a causal mechanism that can be identified as the direct cause of the vast majority of back pain. Unfortunately, short appointments via traditional medical channels simply provide no opportunity to show the patient the cause of his or her pain; nor does it offer an effective guiding plan to eliminate the cause and encourage pain-free movement.

Trainers are experts with movement, specifically with manipulating movements, postures, and loads. These will either worsen an afflicted client's pains or relieve them. In short, the great trainers:

- Assess motions, postures, and loads that are the specific pain triggers.

- Coach the client on movement in daily tasks that avoid the pain trigger to allow it to desensitize and create a client receptive to training that strengthens them, rather than subjecting them to pain.

- Create a progression of exercises to create a foundation for pain-free activity.

The trainers who can skillfully fulfill these three duties will likely never be short on clients--clients will be flocking to their door!

In actuality, we are all capable of becoming our own Back Mechanic.

Back Mechanic, a Guide to Pain-Free Movement

My book Back Mechanic is a step-by-step guide, accompanied by rich illustrations, that is designed to empower both the client and the trainer to become their own best advocates to get rid of pain. As with any result-oriented goal, there is no such thing as a "one-size-fits-all" approach. This book teaches you the pain triggers that are unique to the individual and how to avoid them, as well as provide a comprehensive guide to each set of corrective exercises that will adjust movement patterns and rebuild tolerance and strength.

In fact, 95 percent of my referred patients had once been told their only remaining option was surgery, but after following the methods outlined in this program, they were able to avoid it.

In this book, you'll find the essential steps to reduce pain and learn how to:

- Assess the specific pain triggers.

- Remove the triggers from daily activity by practicing spine hygiene and movement principles (each person is different and the book guides instruction for categories of pain).

- Build spine stability and appropriate mobility in the hips and shoulders.

- Guide progressions in movement patterns, such as pushing, pulling, lifting, carrying, and so on, to expand pain-free living.

- Guide strategies for a pain-free life, such as how to select a mattress, how to have sex without pain, how to address specific conditions such as stenosis and kyphosis, to name a few.

You can find the book and other evidence-based McGill products from http://www.backfitpro.com (worldwide), Amazon, Amazon UK, and Amazon Canada.

Other trainers found these articles helpful:

- The Personal Trainer's Guide to Diastasis Recti by Jessie Mundell

- Easy Exercises to Help Your Client's Lower Back Pain by Dr. Scott Hoar

- Why People Must Squat Differently by Ryan DeBell