If you hate cardio, I get it. In fact, I’ve lived it. I was like you for years.

For many of us, cardio feels like work.

It’s a joyless obligation, like eating plain oatmeal. If we do it, it’s because we think it’s good for us—not because we actually want to.

Typical reasons you’ll hear people say they don’t do cardio:

- “It sucks” - It’s too hard and feels awful.

- “It’s boring” - You do the same thing over and over for a long time. Ugh.

- “It’s not effective” - I tried running once and I still have lovehandles. #FAIL

But those thoughts are misguided.

The real reason we hate cardio is because we’ve failed to be creative. Or because we’re behind the times. Or we misunderstand what cardio really is.

- Why “failed to be creative”? Because there’s a popular misconception that “cardio” means “slogging away on an elliptical for 20 minutes or more.” FACT: Any movement can be made into cardio, with proper programming.

- Why “behind the times”? Because recent technology makes proper cardio training easier and more accessible than ever. Your smartphone plus a heart rate monitor can open up a whole new universe of smarter, more effective training.

- Why “misunderstand what cardio really is”? Because people confuse cardio with its far less interesting cousin, aerobics. (See more in “What is cardio,” below.)

If these errors lead us to avoid doing or programming cardio, that is a problem. Because the benefits to true cardio training are vast.

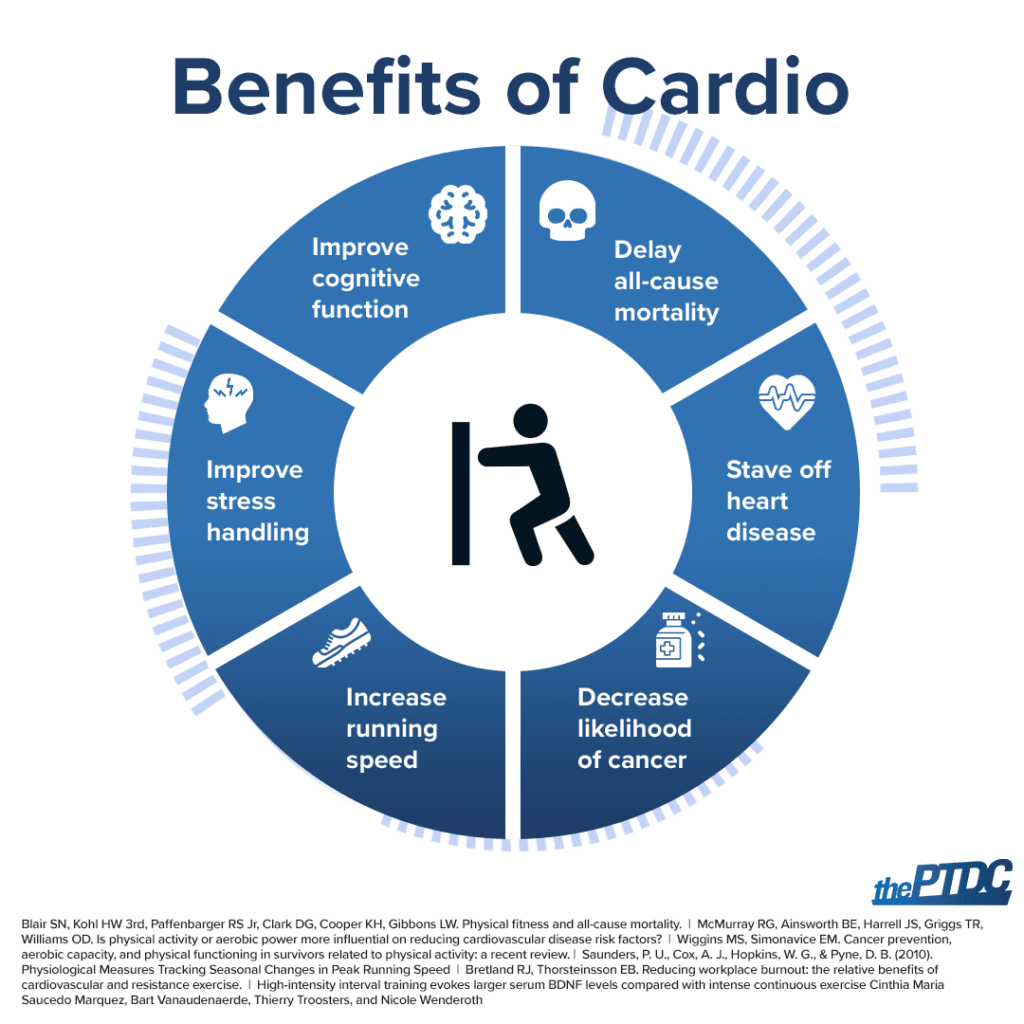

Higher levels of cardiovascular fitness appear to delay all-cause mortality. Translation: Cardio improves the likelihood you’ll live longer.

A stronger cardiovascular system helps stave off heart disease, decreases your likelihood of getting cancer, and increases your chance of survival if you do.

And that’s just a toe dip into the pool of research demonstrating cardio’s benefits. I could hit you with about a dozen other studies that show having a stronger cardiovascular system is helpful for nearly every imaginable domain in life, from being faster for sport to handling stress to cognitive function (a.k.a. how well your brain works).

As trainers, we ought to be concerned with more than just how someone looks or their bench max. Our job is to help build fitter, healthier, longer living human beings. Done well, cardio helps a person make progress on all of those fronts—and build a more muscular, better looking physique in the process.

Therefore, it is in your interest to get off the popular but misguided “I hate cardio” train, and take your clients off it too. In this article I’ll show you how to do that by covering …

Let’s dive in.

What is cardio, really?

Cardiovascular exercise can be anything that improves the capacity of the cardiovascular system—that is, anything that elevates the heart rate to a target level.

While cardiovascular exercise can be considered a form of aerobic exercise, the terms are not synonymous.

Aerobics encompass any form of movement sustained long enough that the body needs to utilize oxygen to fulfill its energy demands. Therefore, everyday tasks such as walking can be considered aerobic if they’re sustained long enough.

Cardiovascular exercise, on the other hand, needs to improve the capacity of the cardiovascular system. In other words: We’re focusing on the capacity of the heart. Which means true cardio requires three things:

- We need to monitor the heart rate.

- Exercises must elevate the heart rate to a target level.

- Heart rate must stay within the target range for an intended period of time.

Working within those target levels, or “zones,” strengthens the heart. It also improves circulation and allows a person to improve the capacity of their cardiovascular system.

This may sound like extra work. Who needs more data in their lives, really?

Many professionals spend enough of their working lives in Microsoft Excel, and don’t need yet another number to pay attention to. But implementing a heart rate monitor, and using it effectively, can be a paradigm shifter for you and your clients.

I’ve experienced this firsthand, both in my own workouts and in training clients. Turns out what we all were doing when we thought we were doing cardio mostly fell into one of two categories:

- Too much - Workouts were suffer-fests as a result.

- Not enough - Workouts felt boring because they were, in fact, under-challenging.

Training with a heart rate monitor surprised me in how much it changed what “cardiovascular exercise” meant. Cardio became much more enjoyable—and effective.

Over time, it helped improve work capacity and strength while shrinking recovery time needed.

Takeaway: By using a heart rate monitor, you produce better results with less suckage.

What about cardio vs. high-intensity interval training (HIIT)?

Just as there is a difference between cardiovascular and aerobic exercise, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and cardio are not the same.

HIIT can only deliver its intended cardio benefits when we monitor heart rate and use the data to dictate intensity and duration.

In fact, it’s not at all uncommon to work far harder than is necessary during HIIT. At least people work way past the point needed to attain the cardiac benefit for which we were striving.

That’s all well and good if the intent of your workout is simply to prove you can suffer. But suffering isn’t necessarily good for long-term compliance.

In the more immediate term, going way too hard on intensity during a HIIT workout can actually undermine your results, since the excessively high intensity may create such muscular fatigue that you cannot sustain it long enough to actually produce a cardiovascular effect.

Going way too hard during HIIT may mean you’re not spending enough time at a cardio-friendly heart rate.

In these cases, the strenuous effort and resulting muscle fatigue may fool us into thinking we got a cardio workout. But in reality, we’ve spent little to no time at a heart rate sufficient enough to be valuable for training our cardiovascular system.

Takeaway: The feeling of fatigue produced during exercise is misleading. Trust data instead.

Rethinking cardio: New and better movements

Now that we have an appreciation for the benefits of cardiovascular exercise, let’s talk about how to implement it in a training plan. For best results I suggest a four-step plan: Explore, Assess, Program, Reassess.

But first: Gear up

Quick reminder: A prerequisite to all of the steps that follow is obtaining a heart rate monitor. Without one, it is not possible to understand how different movements create a cardiovascular demand for your body.

As a general recommendation, I would suggest that you invest in a monitor that may be worn around the chest. While wrist and forearm monitors may work in a pinch, they are less accurate at heart rate monitoring during exercise.

The monitor you choose should relay data to a mobile application, displaying your heart rate in an easily viewable manner as you train.

Some suggestions I have had good results with are:

- Polar H9 or H10

- Morpheus M3

Here’s a quick demo for how to use a Polar H10 during a cardio workout:

Step 1: Explore new cardio movements

Different movements affect different bodies differently. The idea of this step is to wear your heart rate monitor while performing a variety of different exercises. You want to see what movements get you into your intended heart rate zones with the least effort.

Some of the more traditional “cardio” movements include low-impact exercises like:

- Biking (stationary or outdoor)

- Incline walking (treadmill or outdoor)

- Running (treadmill or outdoor)

- Rowing erg

- Ski erg

- Ellipticals

- Versaclimbers

- Swimming

These exercises allow for longer durations of effort before the onset of noticeable joint strain or muscle fatigue. They also allow for easy data collection. And you can easily adjust performance metrics such as speed, resistance, and duration.

However, as we’re rethinking cardio, we ought to take a wider view of what a “cardio” exercise really is—or can be. Because with proper monitoring, any exercise can be used for cardiovascular benefits. That includes …

- High box step-ups (slow, consistent tempo limiting eccentric lowering and impact during landing)

- Various medicine ball throws (i.e., side, chest, between legs toss)

- Jumping pullups (to bar, rope, rings, etc. limiting eccentric lowering)

- Box/step jumps (two-legged, one-legged, side to side)

- Kettlebell swings/cleans/snatches (usually one arm at a time with light to moderate weights and higher reps, switching hands to limit fatigue)

You can combine these moves with two modes of training: (1) dead-start reps and (2) speed repeats.

- Dead-start reps. This means performing a movement powerfully in a concentric direction (propelling upward), but eliminating or substantially reducing the eccentric component (decelerating downward). With this approach, the power put into each rep elevates the heart rate. Cutting out the eccentric spares our muscles, joints, and grip from additional stress.

- Speed repeats involve short periods of moderate-intensity sprints involving multiple repetitions of a movement, instead of repeated isolated reps. These sprints involve cycling through both the concentric and eccentric portion of the movement to ramp up the heart rate. Once we attain this intended heart rate, we then rest and repeat until we accumulate a certain amount of time in our target zone.

Takeaway: Vary the method you use to get your heart rate up. Try traditional low-impact steady-state endeavors, sure. But also try various lifting techniques while manipulating tempo, rest breaks, and the concentric or eccentric portions of the movements to create the effect.

Step 2: Assess

Once we explore which movements can reliably get our heart rates into the target zones, we then need to assess our current state of cardiovascular fitness.

These assessments will allow us to comprehend any progress made once we embark on a program of cardiovascular training.

I recommend using three measurements to track progress:

- Resting heart rate (RHR)

- Heart rate recovery (HRR)

- Estimated maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max)

1. Resting heart rate

You can measure your resting heart rate (RHR) in multiple ways. The most low tech is counting the beats per minute felt by checking your pulse—place two fingers on the carotid artery at the neck or on the radial artery at the wrist. If this is your strategy, I recommend taking the measurement at the same location and same time every day for at least a week to get a good average.

For more high-tech options, wearing an activity monitor with a heart rate function (FitBit, Apple Watch) to bed will give you relatively accurate readings that will be stored in your phone. Again, I recommend getting an average for at least a week to use for later comparison. Once again, consistency is important.

The American Heart Association says a normal range for RHR is 60 to 100 bpm. (That’s a huge range, obviously.) Highly trained endurance athletes can have heart rates in the 40s and below.

Lowering your RHR to some magic number should not, in my opinion, be the goal.

Instead, we simply want to get a baseline of where we are starting and then see the number decrease over the course of several weeks or months as we embark on a cardio program. It’s reasonable to see your RHR drop between 5–10 bpm within 4 to 6 weeks.

| Standards for 1-minute HRR (sources are linked) | |

| Average among elite athletes | 23 |

| Good cardiac health | >20 |

| Normal range for cardiac health | 15-20 |

| Average among active non-athletes | 15 |

| Impaired cardiac function | </= 12 |

2. Heart rate recovery

Heart rate recovery (HRR) is defined as the measurement of how much the heart rate decreases in an allotted time after exercise.

Research on HRR shows it’s a reliable measure of how well our nervous system moves from a sympathetic (“fight or flight”) to a parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) state.

HRR can be calculated simply by measuring your heart rate immediately after exercise, then measuring again after 1 minute. For example, if your HR is 170 bpm when you finish an exercise bout, then 145 bpm after a minute of rest, your HRR would be 25.

3. Estimated VO2 max

While VO2 max is a well-studied indicator of cardiovascular fitness, it can be a complex thing to measure. To capture this number, scientists use high-tech face masks hooked up to a computer. Since most of us don’t have this equipment, we can utilize the Harvard 5-minute step test instead.

To perform this test, use a 16-inch step or bench. Step up and back down at a rate of 30 steps per minute (one second up/one second down right leg, one second up/one second down left leg). Use a metronome app to ensure you stay in cadence. The goal is to keep moving for 5 minutes.

Immediately after you either stop moving or complete the 5 minutes, sit down and count the number of heart beats (at the wrist) from 1 minute up until 1:30. Keep tracking for 2–2:30, and finally, 3–3:30. Then plug the data into the following formula:

Fitness index (estimated VO2 max) = (100 x test duration in seconds) divided by (2 x sum of heart beats in the recovery periods)

For example, if you completed the 5 minutes (300 seconds) and measured 60 beats between 1 and 1:30, 50 between 2 and 2:30, and 40 between 3 and 3:30, your equation would look like this:

Fitness index (estimated VO2 max) = (100 x 300) / (2 x 150) = 100

As mentioned, this fitness index is merely an estimate of VO2 max and usually only 0.6 - 0.8 correlated to actual VO2 max readings. However, as long as this test is done in a consistent manner before and after a period of programming, it can be used to measure improvements.

We can also use these measurements to compare ourselves to others. These standards are listed below:

| Rating | Fitness Index |

| Excellent | >90 |

| Good | 80-90 |

| High Average | 65-79 |

| Low Average | 55-64 |

| Poor | <55 |

Step 3: Program

Okay, once we have an idea of the movements that safely and easily increase our heart rate, and have generated some baseline cardio performance measurements, we are then ready to program for progress.

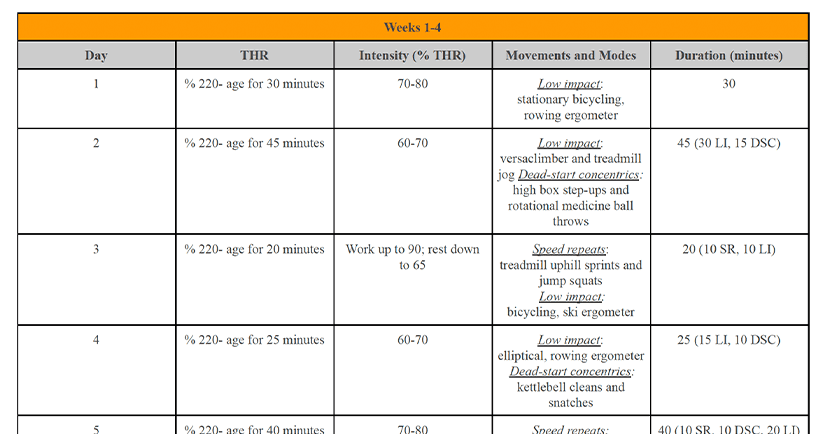

To help us generate a robust cardio program, we need to explore two factors:

- Progressing heart rate zones

- Varying mode, intensity, and duration

Progressing heart rate zones

For programming, we need to take a deeper look at heart rate training zones. For those new to monitoring heart rate during training, you can start with the generic standard “220 minus your age” to get an estimated max heart rate (MHR). This often is the default setting when registering with most heart rate monitoring apps.

Over time, you can use the more advanced Karvonen formula to attain a more accurate target heart rate (THR). This method incorporates resting heart rate (RHR) with age, and leads to heart rate zones substantially higher than the “220 minus age” approach. The Karvonen formula is:

THR = + RHR

For example, where 220 - age = MHR, a 37-year-old with a resting heart rate of 65 would calculate his 75 percent THR as follows:

220 - 37 = 183 for MHR

+ 65 = (118 x .75) + 65 = 88.5 + 65 = 153.5

As we can see, the 75 percent THR of 153.5 is much greater than simply taking 75 percent of the MHR of 183 (~137). Therefore, simply moving from “220 minus age” to the Karvonen method can increase intensity quite a bit.

If you want even greater accuracy, and the ability to adjust THR based on daily stress levels, I recommend picking up a Morpheus. This tool, created by well-regarded strength and conditioning specialist Joel Jamieson, takes into account factors such as sleep, heart rate variability, muscle soreness, and subjective well-being to give you a different training zone each day. In my experience, these adjustments provide more appropriate targets for any given day, and allow for more consistent training without overtraining.

Varying mode, intensity, and duration

In my experience, the most important factor for programming cardiovascular fitness is variability.

This means we want as many options as possible for elevating and attaining a THR for an intended time period. These options allow us to reduce boredom, improve athleticism, and limit the inevitable joint strain that comes from performing the same movements in the same way over and over.

Finding variability starts with exploration, as discussed earlier. Along with varying movements and training modes, we also want to vary the intensity of the heart rate zones attained, as well as the duration spent within them.

Generally, the higher the heart rate zone, the lower the duration, and vice versa. For an example of how this programming all comes together, follow the link for a sample 12-week program.

Download the author's sample 12-week cardio program to see how variation and progressing heart rate zones can come together.

Step 4: Reassess

This final step involves simply re-testing the baselines found in step 2. As a review, we found baselines for the following:

- Resting heart rate (RHR)

- Heart rate recovery (HRR)

- Estimated maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max)

We will be routinely reassessing our RHR and HRR at least weekly. For the estimated VO2 max test, we can re-measure it about every four weeks to track our progress as we move through the program.

As a word of warning, try not to get discouraged if progress with these numbers isn’t linear. There are many variables at play (sleep, stress, testing position).

Therefore, when reassessing, pay attention to larger trends demonstrating obvious progress, rather than small changes day to day. Many heart rate tracking apps, such as Polar, Fitbit, and Morpheus, plot and save the data from your workouts making these trends easy to visualize.

Furthermore, progress is often felt qualitatively as much as quantitatively, so keep an eye out for the following changes:

- It feels easier to be consistent with training.

- It feels easier to attain or maintain the THR zones programmed.

- You feel more athletic by being more proficient with a wider variety of movements.

Conclusion: Final thoughts on better cardio

Cardiovascular exercise is too valuable for our health to be “hated.” The popular disdain from cardio stems from misunderstanding or a lack of creativity. As a trainer, you can do better—and you’ll provide much better service to your clients as a result.

The simple acts of monitoring your heart rate and training within heart rate zones will completely change your mindset. Start simple with the “220 minus your age” and then progress to more accurate (and challenging) heart rate training methods.

Remember: Any movement can be cardio if you’re paying attention to your heart rate. Set zones and stick with them during workouts. Varying intensity, duration, and movement will help your clients feel like younger, healthier versions of themselves.