The last 10 years have seen a significant rise in the amount of research in social networks’ influence on the spread of obesity. One such research, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggests that real-life social networks impact obesity by “normalizing” a heavier body weight and influencing behaviors that are associated with weight gain.

The Yale professors, Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler, examined the spread of obesity within Framingham, Massachusetts and observed that an individual’s weight gain can influence a friend, a friend of a friend, and a friend of a friend of a friend. Also, a person’s chance of becoming obese increased if siblings or spouses had become obese. So if we want to make a dent in the obesity issue, we must more closely examine these more subtle influences that social networks have on weight and weight-related behaviors.

There are two ways social networks can have an impact on a person’s body weight. First, everyone has a certain reference value for their ideal weight, perhaps an old high school or college weight we would like to achieve, or in comparison to our peers. Our social network can set the standard for what is a normal or “acceptable” weight. For example, if most of your friends and family members are overweight or obese, you may have to gain a substantial amount of weight before a sufficient discrepancy between real and ideal states exists. This only delays the need to make the necessary life changes.

Secondly, our peers, colleagues, and family may disrupt or outright derail weight loss-promoting behaviors. For example, in social situations, your clients may eat more sugary sweets or drink more soda and alcoholic beverages than they intend to.

Social groups dictate the reference point of a normal weight.

As I alluded to earlier, peer groups set a standard for what weight is considered normal and subsequently change the point for when a client’s current weight would compel them to change his or her behavior. Here is an example of how this may work:

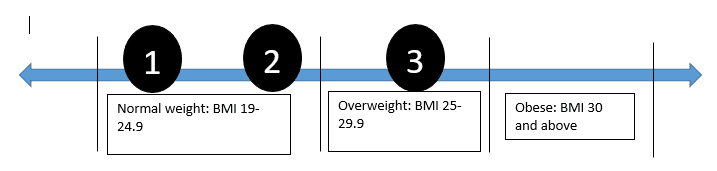

A normal body mass index (BMI) is in the range of 19-24.9; an overweight BMI ranges from 25-29.9 while obesity is considered 30 and upwards.

Imagine three different peer groups. In group one, members have an average BMI of 21. In group two, members have an average BMI of 24, and group three is made up of an average BMI of 28. Despite being overweight, those members in group three have no social pressure to change behaviors. However, if someone from group one were to gain body fat until his BMI matched the norm of group three’s, he would feel sufficient social pressure (just from comparison) to lose weight.

Same weight, different levels of social influence to change. In other words, we tend to group and bond with those similar to us.

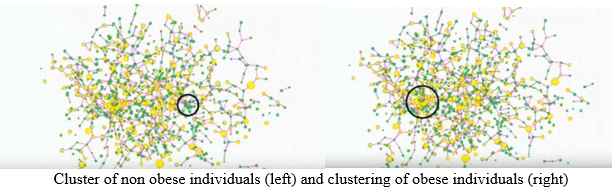

In social psychology, this is called homophily. In their research, Christakis and Fowler examined that over time obese and leaner individuals would form their own separate social clusters. That is, healthy people hang out with other healthy folks, while obese or overweight people hang out with other obese or overweight friends.

And by virtue of their social networks, healthy people are more likely to be exposed to new health innovations or trends more frequently than those in an obese cluster. This greater exposure leads to greater adoption of beneficial behaviors, and the same holds true for unfavorable behaviors. People tend to mimic those who are similar to them, so the behaviors of leaner individuals do not necessarily lead to adoption by overweight or obese individuals, who may see themselves as part of a different group.

But there’s good news, and this is key.

According to an experimental study: If most of your client’s peers in your social network are overweight or obese, your client’s adopting health behaviors can have a positive influence on them. If they see your client succeed and try new health behaviors, they may believe they can do so as well. Thus, by changing behaviors you can encourage your client to make positive impacts on their own social network.

That idea can be very empowering for your client.

Viewing peer behavior as a disturbance to goal-directed behavior

In social psychology, descriptive norms describe what normal behavior entails. If your client has set weight loss goals, but the normal behaviors of his or her peer groups do not support this he or she may run into what is called disturbances. Disturbances are considered anything that gets in the way of acting on behaviors that work toward a goal.

Here are a few examples:

Scenario 1

Goal: Your client wants to lose 20 pounds. In order to do this, she has decided to bring her own lunch of cut peppers and two hard-boiled eggs to work.

Disturbance: A co-worker whom she usually has lunch with invites her to a pizzeria that she used to go to.

Scenario 2

Goal: Your client wants to lose 30 pounds. He has decided to cut back on drinking alcohol.

Disturbance: A friend comes over for dinner and brings a bottle of wine. She pours a glass and hands it to your client. Your client tries to say, No, thank you, but she pressures the client. Your client takes the glass.

Scenario 3

Goal: Your client wants to eat healthier to lose weight. She has decided to cut out any sweets, such as cake, pastries, and any sugary drinks.

Disturbance: Your client is invited to a family party. There is banana walnut cake with vanilla frosting, which happens to be your client’s favorite cake. Someone offers a piece of it to your client.

How would you advise your client in each of these scenarios?

There is nothing wrong with “moderation.” Maybe your client has one slice of pizza, half a glass of wine, and a sliver of cake. In an ideal world, this is how it would work. The problem is when your client is not able to make the “obvious right” choices a majority of the time.

In order to gain back control, suggest to your client to form some self-regulation strategies. In scenario three, for example, your client may form a plan based on knowing what desserts or food may be at the party. You can advise your client to decide to say “Rather than eating cake, I will have a piece of fruit.” An alternative would be to simply stay away from the “trigger food,” which is the same as saying, "don’t go in the same room as the cake."

I’d also like to share a particularly effective strategy that I learned from Dr. Robert Cialdini, the author of Influence. Here’s what it looks like. Oftentimes if your client does not conform to norms, they may receive resistance from their peers.

“Are you sure you don’t want a piece of cake?”

“Why aren’t you drinking?”

“Well, I don’t want to walk to the pizzeria alone. Just come with me today.”

And so on and so forth.

These seemingly harmless comments are a form of peer pressure that causes your clients to cave and perform behaviors that are counterproductive to their goals. If they don’t want to have that cake, eat that pizza, or drink any wine, have them try saying the word because... and following it up with a reason.

Let’s look at the first scenario again and see what adding because… can do.

Situation 1

Colleague: “I’m going to Mark’s Pizzeria for lunch. Want to go with me?”

Your client: “No, thank you, I’m not hungry.”

Colleague: “Well, I don’t want to walk to the pizzeria alone. Just come with me today.”

Situation 2

Colleague: “I’m going to Mark’s Pizzeria for lunch. Want to go with me?”

You: “No, thank you, I’m not hungry because I already had my lunch today.”

Colleague: “Okay, I’ll ask Tom.”

This might sound scripted, but I have clients that have found success with this strategy. In fact, here is a real-life example of a client who was shocked by how well this strategy worked (and continues to do so).

Situation 1:

Boyfriend: “Do you want a glass of wine?”

Girlfriend: “No, thank you.”

Boyfriend: “Are you sure you don’t want any?”

Girlfriend: “Yes.”

Boyfriend: “Here just have a little.” (At this point, boyfriend pours half a glass of wine.)

Situation 2:

Boyfriend: “Do you want a glass of wine?”

Girlfriend: “No, thank you, I’m good because I’m actually feeling a little dehydrated.”

Boyfriend: “Let me get you a glass of water!”

And just like that, you can help your client diffuse these tempting situations. Self-regulation strategies for social situations do not mean your client has to completely deprive himself from the fun of having food and drinks with friends and family. These strategies also work for establishing moderation. Here are examples:

“If I am going out drinking with friends, I will drink a glass of water between each drink.”

“If I am going out to eat with a colleague, I will ask the waiter to box up half of my meal.”

“If I am at a family party and there is cake at the table, I will split my piece with my niece or nephew.”

Clearly, using the because… strategy effectively takes away any chance for the other party to resist.

The point is, make sure your clients can recognize the influence of their overweight and obese friends on their desire to change. When they make their own health changes, they can also positively impact their own social network. If your clients can receive less peer pressure by forming self-regulation strategies like the ones we mentioned, they are less likely going to cave in to social situations.

References

1. Christakis, N.A., & Fowler, J.H. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 370-379.

2. Ogden, C.L., Carroll, M.D., Kit, B.K., & Flegal, K.M. (2014). Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 311(8), 806-814.

3. Centola, D. (2011). An experimental study of homophily in the adoption of health behavior. Science, 334, 1269-1272.