There’s a parable about a Portuguese fisherman. You’ve probably heard it before.

Goes like this:

This fisherman’s boat always had several large, fresh fish in it. An American investment banker on vacation asked the fisherman how long his catch took him.

“Only a little while.” The Portuguese man replied. “I have more than enough to support my family.”

The American then asked what he did with the rest of his time.

“I sleep late, fish a little, play with my children, take a siesta with my wife, and stroll into the village each evening where I sip wine and play guitar with my friends.” The fisherman said.

“You should buy a bigger boat.” The American replied. “Then you’ll make more money and be able to afford a fleet of boats. And eventually you’ll be able to move to the big city and open your own cannery.”

The fisherman asked how long this would take.

“15-20 years” replied the American.

“Then what?” Asked the fisherman.

“Then you will be rich and can retire.”

“And what would I do then?” The fisherman asked?

“Then, my friend, you will have no worries. You could move to a small coastal fishing village where you would sleep late, fish a little, play with your kids, take a siesta with your wife, and stroll to the village in the evenings where you could sip wine and play your guitar with your friends.” Said the American.

—

“Enjoy the process.“ Is advice we hear all of the time.

“Do the verb in order to become the noun.” They say. “Relish the experience.” “Savor the journey.” “Cherish the adventure.” You’re told.

And it’s all good advice in theory. Without application though, it’s useless. First, some helpful terminology. Then, a new spin on an old story.

—

In linguistics, there’s two types of activities: telic and atelic.

Telic activities aim at terminal states. Getting married is telic: it’s done when you’re wed. Writing a book is telic: it’s done when your phalange fingers the final key. Driving somewhere is telic: it’s done when you arrive.

Atelic activities don’t aim at a terminal state. It doesn’t drive towards finishing. It describes the process. Which never completes.

The same activity done differently can be either telic or atelic. For example, walking home is telic: home is the end state. Going for an aimless walk, on the other hand, is atelic. It’s true that you will eventually stop walking but aimless walks are never completed.

In our future-focused society, we’re trained to be telic. Always be striving to get there, never here. Thinking about the past, driving toward the future, while leaving the present curiously unoccupied.

I live in a small Mexican fishing village most winters.

One morning, at the gym, I met Isaac. A Mexican-American. He was born in town. Went to College in California. Got some finance degree. Then came back.

He works out every morning with his girlfriend and dog.

At sunset, you’ll find him playing Spikeball on the beach with friends.

During the day he works at the best taco spot in town.

I’ve never seen Isaac without a smile. He’s fit, eats fresh fruit, gets free tacos, and is surrounded by people that he loves.

But a part of me also knows that I wouldn’t be able to do what he does. And I also wonder how long he’ll be able to do it.

It’s too perfect.

Idyllic days on repeat where the sun shines, the food’s delicious, and the activities are great are nice in theory. Without contrast, however, desensitization sets in and it leads to burnout just the same.

And so, I’m left with a paradox. Call it the false allure of early retirement. Of giving the middle finger to the real world and replacing it with beautifully perfect days on repeat. The problem with the Portuguese fisherman story.

On one hand, a project-driven life is no way to live. But there’s also no way to live other than to be driven by projects.

—

We obviously shouldn’t wait to retire to buy a sailboat and sail around the world.

Maybe we won’t ever be able to afford it.

Or something tragic happens and we die.

Or maybe we’ll finally make it to those golden years and buy a sailboat only to discover that sailing sucks. Or that golf becomes horrendously boring when you do it more than three times a year.

Here’s my challenge.

I want to fall in love with the process and ignore the outcome. But I can’t. I just can’t. I’m always thinking about the outcome. Want to know what I was thinking at 11:25am on October 28, 2024. As I typed these words for the first time. I was thinking, “will my next book that I wrote this section for be a success? Will it sell? Will anybody care?”

I once produced three books. I say produced because even though my name is on them, I didn’t write them. The books made some money. Not a lot. Enough to be a good business decision though. But I learned nothing from the experience. I gained nothing from the experience.

So now I don’t care about the books enough to even display them on my shelf. They mean nothing to me. They did nothing for me. Purely telic. A strategic business decision. A means to an end.

We had plans to do at least five books in the series. After three I said enough was enough. I thanked the talented ghostwriter and paid him a severance. Then swore that it was going to be the last time I ever did the work for the money. Because even though I did get some money, I got nothing from the work.

Writing my next book, on the other hand, which will be called The Obvious Challenge, has helped me become more of the father, husband, friend, spouse, and boss that I want to be.

It's about intentional life design. I’m writing about being more happy, grateful, and adventurous. I’m reading and listening and thinking about those things constantly throughout the day. As a result, this work has changed me. It has already helped me to become more of the human I want to be.

The week after I handed in the first draft of my next book, my previous one called The Obvious Choice got released. That just happened. It sold well out of the gate. Didn't make the New York Times list as a bestseller but actually sold more than all the books that did make the list past the sixth spot. Choice was also met with critical acclaim. Tons of incredibly positive reviews.

Want to know what's been weird about these past two weeks though?

I've felt sad. I never feel sad. But, for the first time in my life, I felt sad. Like, I didn’t want to get out of bed. That no matter how much accounting I did of everything good going on in my life, it didn’t matter.

I’m living in Mexico. There’s music and tacos and people that I love around. Lots of people were saying nice things to me. And about me. Despite this, my world felt grey. I lost my appetite. Was exhausted. Had a short-temper with my kids. Every day, a malaise. Alison even took me to the medical clinic. The doc checked me head to toe. Didn’t find anything. That’s because I wasn’t sick. At least, not in the traditional sense.

For three years, I worked on The Obvious Choice. Then the first physical copy arrived. And I held it. Then release day came, and people bought it. And there was nothing more for me to do. The job was finished.

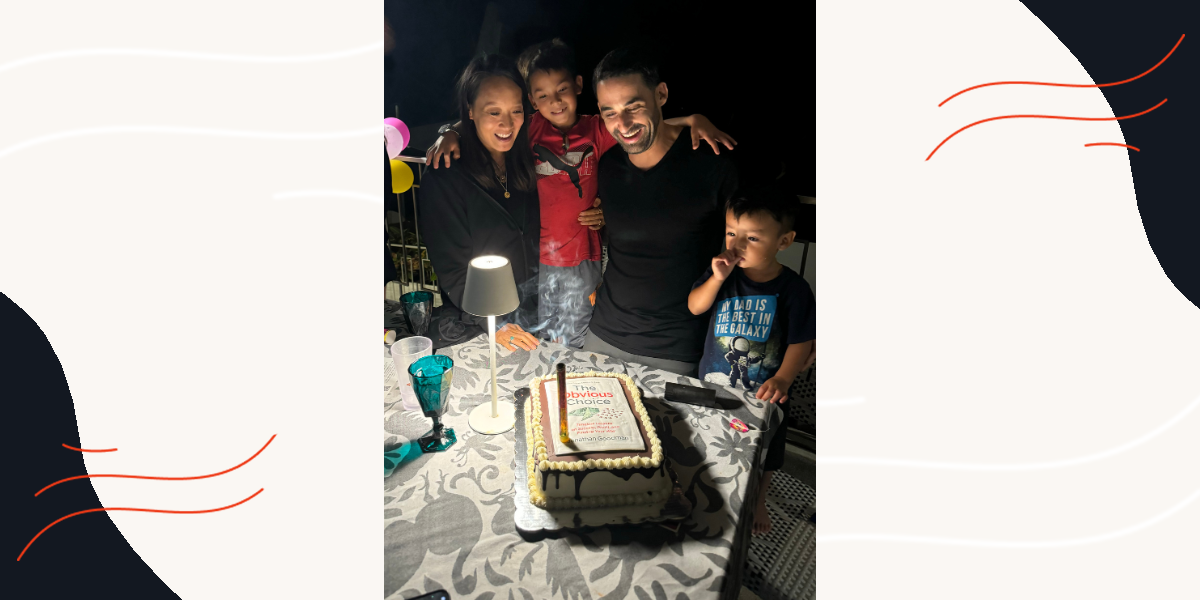

Alison organized a party the night of the release. Invited our friends. Had spanish guitar music playing in the background. Got a cake made with a picture of the book. All the time I should have been soaking in the celebration and praise, happy . . . and proud . . . But, I felt neither of those things. Instead, an emptiness. Like, “that’s it?”

Here’s what I've learned:

The rewards you get from the outcome of any finished project are never as great as the rewards you get from the project itself.

No amount of praise, prestige, or profit after the fact replaces the internal growth when you’re stuck in the messy middle of something.

It's ok to be driven by projects. Good, even. So much so, that the worst thing that can happen is that you don't have one bearing down on you.

I got out of the funk by getting back to work.

The Obvious Choice is now something I did, not something I'm doing. On to the next one.

The smartest thing that I did when I handed in the final manuscript for Choice last year was start the next book. And the smartest thing I could do when I finish the one I'm working on now is to start the one after that.

When you find the right project to work on, the worst thing that can happen is that you finish it. And the first thing you should do when that happens is start the next.

Maybe that’s not healthy. Maybe it’s better to rest on your laurels for a bit. Soak in in. Rest. Recharge. But I’ve found that the body is like a car battery, it needs consistent movement to stay energized.

Doing work that matters is challenging. Work that matters to you, not others. That’s the only litmus test that matters. Work that makes you better while you’re doing the work, not for it being done.

If you cannot explore within your work, no matter how big or important your work is, or how much money it makes you, you will burn out and it will feel empty.

If you finish your work and have nothing else to challenge you, no matter how big or important it is, or how much money it makes you, you will burn out and it will feel empty.

You must find the atelic within the telic.

Waking up each day in the same bed. To the same perfect weather. With the same routine. With no stress. With no challenging project forcing you to figure some shit out. It’s a miserably empty existence. You need the work.

I used to love the parable of the Portuguese fisherman. Then I took on the task of writing this book. Which forced me to think deeper about the story. That’s when I thought back to Isaac. The lesson he taught me was that the parable of the Portuguese fisherman is nonsense. And maybe the American businessman isn’t as crazy as he’s made to appear.