The coronavirus hit the fitness industry especially hard.

Gyms closed with little to no warning, leaving trainers scrambling.

But not every coach was devastated. Some earned more money and expanded their businesses.

The following five case studies show you how they did it.

Read them to learn how you too can build a resilient online fitness business that not only survives tough times, but actually thrives.

How to Make Money as an Online Trainer

Case study #4: How Nelao helps trauma survivors with their fitness through online coaching

---

Case study #1: Leanne Salisbury

How a scientist and single mom escaped a toxic work environment to become a successful hybrid coach

It was a slow day at the lab, and Leanne Salisbury asked her boss if she could use an hour of paid time off to take her teenage son to a meeting to help plan his college education.

She thought it was a reasonable request, and was surprised when he said no.

He told her to use the time to defrost the biomedical lab’s freezer, where they kept the ice used to cut the human tissues they tested for cancer and other diseases.

That afternoon she got a call from her son’s school, demanding that she pick him up because he’d been suspended for acting out.

“I broke,” she recalled in an Instagram post. “I told the boss he could kiss my ass, in front of the entire room. I left and had a complete breakdown in my car.”

Because she worked for the National Health Service in Liverpool, England, she wasn’t immediately fired, as she would have been in just about any private-sector job. (“At the NHS, you have to kill about 10 people to get fired,” she jokes.) They let her transfer to another department.

But she knew her life had to change. As she wrote on Instagram, “This was the moment I knew I had to create my own job, live my own life, and stop being everyone else's puppet.”

From scientist to personal trainer

Fitness was an unlikely career choice for Salisbury. She didn’t even own a pair of sneakers until she was 27.

But then she got a wake-up call.

“One of my friends in the laboratory died of cervical cancer,” she says. “It really made me assess a lot about my life.”

She started running, figuring that “it shouldn’t be too hard to run for 30 minutes without stopping.”

It was. She nearly threw up at the end of a charity 5k run. But the experience made an impression. “That’s one of the first times I saw you can push through,” she says.

In 2013, the year she told her boss to kiss her ass, she got a personal training certification and began coaching clients part-time—first in their homes, then in a studio where she rented space by the hour, and then in a commercial gym, an environment she says she “absolutely hated.”

She left her day job in 2015 with only three months of severance. It was make it or break it time.

Building her client base was “a huge rollercoaster,” she remembers. She’d spend months growing her clientele, then switch venues and have to build it back up again.

Finally, she hit on a solution. Two of them actually:

- She opened a fitness studio about 20 minutes from her home.

- She turned her son’s bedroom (he had recently moved out) into a workout space for coaching online clients.

The online coaching breakthrough

Salisbury enrolled in the Online Trainer Academy Level 1 Certification course in 2018. She’d been a member of the Online Trainers Unite Facebook group for a while, but resisted making the leap to OTA.

OTA reminds her not to get distracted by shiny objects, she says. “I go back to it all the time. When I feel myself going off on a tangent, I’ll book a call with the coaches.”

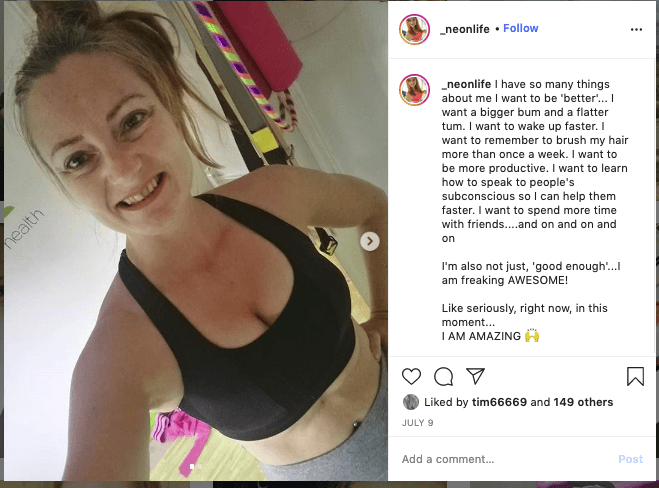

Salisbury’s Instagram feed is a masterful example of connecting with clients and prospects by mixing deeply personal admissions of her past struggles with upbeat stories about her current life and work.

Salisbury’s Instagram feed is a masterful example of connecting with clients and prospects by mixing deeply personal admissions of her past struggles with upbeat stories about her current life and work.

One consistent message: Your life doesn’t have to suck. You can choose to make it better.

“I’m not perfect,” she wrote in one post, “but I'm healthier, happier, have more friends, have more fun. ... I get to help people all over the world with their food, training and mindset. And I'm really good at it, because I'm sharing the tools that helped me, not just what I listened to in a podcast. I've been in that place where it's all just far too much, you know?”

---

Case study #2: Jim Gazzale

How a part-time nutrition coach went from charging $95 a month to $1,500 for three months, and adds a new client every week

From the outside, Jim Gazzale appeared to be a successful online trainer.

His Facebook description of his business—“I help moms over 40 lose up to 20 pounds in 12 weeks by drinking wine and eating whatever they want”—seems irresistible. His website shows a suite of services encompassing strength, endurance, nutrition, and lifestyle coaching.

What you couldn’t see was a struggling part-time nutrition coach who made so little profit from coaching that he wasn’t sure if he could afford to continue.

His day job was safe and steady. But it wasn’t enough to support his young and growing family.

If he couldn’t generate more income from coaching, he’d have to find another part-time job.

But instead of giving up, he doubled down, stretching his finances to the limit to learn a more profitable system to train clients.

The evolution of an unlikely nutrition coach

Gazzale and his wife, Karen, are broadcast journalists.

As an on-air talent, Karen had plenty of incentive to stay in shape. But Jim had never found a fitness or diet regimen he could stick with. “I knew I was overweight,” he says. “I would follow her to a workout here or there. But I hated it.”

He found his motivation in 2015, when they joined a gym with the goal of getting in shape for their wedding. And he stayed with the program after the wedding, even though the results were disappointing.

That all changed in early 2016, when they hired the owner of the gym to be their nutrition coach.

“I followed it to the letter and got absolutely shredded,” he says. “That opened my mind to what’s possible. I was strong, I was confident, I was fearless. It was really a life-changing thing.”

It was so life-changing that he and Karen decided to help other people change their own lives. They get certified through Precision Nutrition, set up a website, and waited for clients to find them.

They quickly realized it takes a lot more than the desire to help people. It only works when you combine your knowledge and good intentions with marketing and business development.

Finding an online training model that works

Thinking “how hard could this online coaching thing be?” (sound familiar?), they spent that year “trying to build the business flying by the seat of our pants,” Gazzale recalls. “We took our lumps early on trying to figure the whole thing out.”

They had what looked like a breakthrough in 2018, when they helped a woman with a big Instagram following lose weight. Her story brought in 30 clients virtually overnight.

“But I didn’t have a way to service them,” Gazzale says. “After a few weeks, they all kind of dropped off.”

That’s when he started looking at the Online Trainer Academy.

“We were living paycheck to paycheck, sometimes even operating in the red,” he says.

“I knew I had to get a part-time job. Why would I want to spend my time doing something I didn’t enjoy? That’s where the impetus to make this a profitable business took shape.”

Gazzale saved his pennies, and enrolled in OTA, and never looked back.

Balancing a family, a full-time job, and part-time nutrition coaching gig required structure that Gazzale couldn’t build on his own. He leaned into OTA for help and hasn’t looked back.

“Having a structure in place was the biggest thing I got from OTA,” he says. “Some months were better than others, but I was confident it could grow over time, rather than fizzling out like that influx we saw in 2018.”

It was working, but not as well as it could have.

The problem, he says, is that the business “was structured to always be a side hustle.” Each of his clients paid about $95 a month for a la carte services, which meant each of them required more or less the same amount of attention.

He needed a way to scale it up so he could coach more clients in the same amount of time. To do that, he decided to once again stretch his finances to the breaking point.

How a high-ticket coaching program pays off

Gazzale was one of the first coaches to be accepted into the Online Trainer Academy Level 2. He had to spread the enrollment fee over three different credit cards and bank accounts.

Level 2 teaches coaches how to create, market, and operate a premium coaching service. It’s for online coaches who already have a strong foundation, either from OTA Level 1 or somewhere else. His clients now pay $1,500 for the 12-week program, and he’s been adding four to five new ones a month.

He’s also learned to follow the same advice he gives his clients. Be patient. Be consistent.

“I have to remind myself to replay the conversations I have with clients and apply them to myself,” he says. “It’s why I’ve had a good run of success lately.”

---

Case study #3: Gil Mesina

How an engineer found meaning in his work as a part-time coach and trained 340-plus clients in 19 countries

Gil Mesina is an electrical engineer, a job he’s been doing for 20 years and counting.

It’s the kind of steady, high-paying gig a lot of people fantasize about, especially if they happen to be math nerds with boatloads of student debt.

“It’s a great job, with great people,” he says.

But …?

“Fitness is my true passion.”

It just took him a while to figure out how to act on it.

From dancer to online trainer

Mesina met his future wife through bachata, a Dominican dance style, where they competed internationally. His passion for fitness emerged when he got in peak shape for their final contest.

By then he was on the cusp of 40 years old, and the grind of training for competition had taken the fun out of dancing. But he’d found a new calling.

“Dancers started coming up to me and asking me to help them,” he says.

In early 2016, he trained four male friends from the dance world—all online, all for free. (To this day he’s never trained anyone in person.)

“One of the guys said, you should try it with females,” he remembers. The four women he recruited helped him launch a thriving online training business.

Mesina’s first four clients. (His wife is in the middle.) After showcasing their results, Mesina says, “a lot of people started reaching out.”

He began running groups for 10 to 15 clients, and their results led to even more referrals.

Now that it was a business, he looked for ways to run it more efficiently. John Berardi, cofounder of Precision Nutrition, told him about Jonathan Goodman and the Online Trainer Academy.

“What I saw from Jon and his tribe is no-nonsense,” he says. “There’s a trust factor because I never felt Jon was there to sell to me. He never said ‘buy, buy, buy.’”

Mesina launches four 12-week group challenges each year, using the same basic program each time. After averaging 20 clients per group, recent challenges have brought in about 30.

His marketing is mainly word of mouth, much of it generated when he shares his clients’ before-and-after photos and testimonials on Facebook. “Just do a damned good job, and make sure everybody knows about it,” he says, quoting one of Goodman’s favorite exhortations.

Until recently, he’d never considered training clients who want to continue beyond the 12-week challenge, even though the demand was there. “My philosophy was, after 12 weeks, you’re done with me. You’re good to go.”

Soon after COVID-19 hit, the OTA coaches convinced him to add a “legacy” group.

Training those clients along with his challenge groups would seem to be a full-time job, but Mesina still manages to run it in his spare time.

“A lot of it is already automated, so it doesn’t take as much time as people think,” he explains. As for the legacy clients, “They don’t need as much hand-holding because they know how it works in terms of accountability.”

That said, he is considering his exit strategy from his original career. “It’s something I’m working toward,” he says.

“The engineering job is still really good. But fitness is my passion.”

---

Case study #4: Nelao Nengola

How Nelao helps trauma survivors with their fitness through online coaching

“I didn’t ask to be in this stupid-ass survivors club,” Nelao Nengola once said in a powerful video. “I didn’t sign up for lifelong depression.”

What she survived is a sexual assault when she was a high school student in Namibia.

Until recently, she wasn’t sure how to address the attack that so profoundly changed her life. She first shared her story a few years ago, but stopped when she realized she wasn’t ready.

“I used to think you heal by telling,” she says. “But I realized not everyone deserves to hear your story.”

Nengola decided to start sharing it again when she discovered an audience who deserved to hear it: assault survivors interested in fitness.

It made perfect sense.

Like many survivors, she rapidly gained weight following the assault, part of a downward spiral both caused by and feeding depression.

Running, Pilates, and eventually strength training helped her regain some control over her body and emotions. She got certified as a personal trainer shortly after.

Building a career beyond borders

Namibia is a big country with a small population.

The challenges, though, go far beyond population. Sub-Saharan Africa has the world’s most extreme income inequality. That means every fitness pro competes for the small handful of people who can afford to pay for personal training.

Nengola started out in a franchise gym in Windhoek, the capital, but left that job after three months to open her own training studio.

“It was awful,” she says. “I was training from 5 in the morning until almost 10 in the evening sometimes. I loved what I did, but I had no energy for anything else at all.”

By the time she closed the studio, after two and a half years, she was deep in debt and looking for a way to survive as a personal trainer. For a while she ran group fitness classes in a gym owned by a prominent local businessman. But the early morning hours “reminded me of all the things I hated about training.”

Online training was the obvious answer. She signed up for the Online Trainer Academy within a week of finding it. “It seemed to be exactly what I was looking for,” she says.

Nengola in her home, where she now runs her online business—filming workouts, coaching clients, and creating content.

That’s when she realized there was a natural audience for her message, if she was willing to start sharing again.

“When I asked myself who I’m best suited to serve, and what would be in line with my purpose, it was trauma survivors,” she says. “Fitness is what pulled me out of my dark place. Why shouldn’t I teach other women that they can do this as well?”

She currently has online clients on three different continents—North America, Europe, and Africa—and no longer trains anyone in person.

“The way I see trainers here grinding, I could never go back to that,” she says.

---

Case study #5: Jesus Acuña

How a gym owner increased his income after the pandemic forced him to close his facility

Timing is a mysterious thing.

If you try to do the perfect thing at the perfect time, odds are you’ll fail. The only way to ensure success is to put things in place before cataclysmic events happen so when they do, you’re prepared.

Perhaps this is why Jesus Acuña, owner of Resilient Fitness in Tucson, Arizona, has the most appropriate gym name in history.

On March 13, he got the call to shut down his gym because of the pandemic.

“That was a punch in the gut,” he says. “They gave us maybe eight hours’ notice. I didn’t sleep that night.”

But when he got up the next morning, he realized it might actually be a blessing in disguise.

An injury, weight gain, and busting his butt in the gym

Acuña started lifting as a high school football player in Tucson. “The technique was crap,” he acknowledges. “But the idea was, if you bust your ass in the gym, you’ll beat the other guys.”

A shoulder injury and corresponding recovery caused him to gain 40 pounds. And he continued packing it on after he returned to the weight room.

By his senior year of college, he estimates he weighed 300 pounds—more than 100 pounds above his pre-surgery weight.

That led to his lowest moment. While training a group of young athletes, one of them said, “Hey, I bet your fat ass can’t do this. Why are you making us do it?”

He lost 20 pounds the next month, on his way to losing all the weight he’d gained.

The next 10 years were the typical grind—five years as an independent trainer, followed by five at a powerlifting gym, which he eventually managed.

In July 2019 he opened his own studio gym with two clear goals:

- “I had to be able to make the money I wanted to make.”

- “I had to do it on my own time.”

And for the first seven months, it worked exactly as he planned. He got to the gym at 9 a.m., went home at 7 p.m., and made $7,500 a month “working as much as I allowed myself to.”

The only problem was, his business was already maxed out, and didn’t know how to ramp up.

When preparation meets opportunity

At a fitness event in 2011, someone recommended Ignite the Fire, Jonathan Goodman’s first book. Acuña read it, started following the PTDC, enrolled in 1K Extra (the precursor to the Online Trainer Academy), and eventually became a Certified Online Trainer.

But online training was still a small part of his business in January 2020. His gym was going well and, like so many of us, he had no idea what was about to happen.

When he got the pandemic shutdown announcement and suffered through that sleepless night, he saw the solution right there on his computer screen. Why couldn’t he offer his group workouts on Zoom?

He contacted his gym members and told them the new plan. “Maybe four or five clients said, ‘Hey, we’re going to stop,’” Acuña says. But the rest of them thanked him for setting up the online system and not leaving them to figure it out for themselves.

In March, 2020, when the first shutdown happened, he made $10,000 online. (The most he had ever made with his studio before the pandemic was $8,000 a month.)

His income rose to $11,000 in April and to $12,000 in August. Through all the twists and turns, with his gym reopening and then closing again, his revenue has remained higher than it was before the pandemic upended his business.

More important, he found a workable model that allowed him to grow his business without canceling his life.

It worked because he was prepared (even if he didn’t quite realize it at the time), and the result is more profit without sacrificing any time with his family.

The Acuna family repping the Resilient Fitness brand.

But there’s one more twist to the story.

On June 27—Father’s Day—Acuña noticed he was struggling to breathe.

He assumed it was because of a wildfire in the local mountains.

When he woke up the next morning, the breathing difficulty was accompanied by a migraine and aching joints. “I felt like I was hit by a truck,” he says. A test confirmed that he had COVID-19.

He was flat on his back for the first three days, and mostly out of commission that first week.

He started taking walks the second week, and thought he was healthy enough to train the third week. The headaches convinced him to wait another week. “I started lifting heavy again, and felt fine,” he says.

His three weeks of illness and recovery are a wakeup call to all the fitness pros who believe young, fit, healthy people are somehow immune.

“People reached out and said, ‘You’re the healthiest guy we know!’” Acuña recalls. If he could get this illness, anyone can.

But he knows it could’ve been worse.

“When I was 300 pounds, I used an inhaler daily,” he says. “I had asthma. Getting COVID in that condition would’ve ruined me. I have no doubt about it.”

Acuña didn’t know that he’d contract a potentially deadly disease when he lost all that weight. But the fact he prepared his body may have saved his life, just as his OTA certification prepared his business for a potentially catastrophic closure.

It’s a double endorsement for the value of preparation meeting opportunity. And it illustrates how smart it was to call his gym Resilient Fitness.