Editor’s note: A version of this article originally appeared on the author’s website.

The personal-training profession is at a crossroads. It’s too easy to get certified (unless you think one weekend of effort is a legitimate test of your knowledge and training skill), but too hard to stand out.

In the age of entitlement, too many people come into our profession with the idea that instant success is the only indicator of a job well done.

I can’t count the amount of emails I’ve received over the years from 22-year-old trainers who, in their second year as fitness pros, want to know what they have to do to write for popular websites, or present at conferences and seminars, or train celebrities and pro athletes, or just generally be recognized as a popular and respected coach.

My answer is predictably disappointing:

I’m 31, and I’ve been doing this for 11 years. In that time, I’ve seen one consistent trait among the most successful and legitimate fitness pros: They put in the time. They didn’t start out training high-profile clients and elite athletes, or lecturing at Perform Better, or getting quoted in Men’s Health. All those things came after a million steps the rest of us never saw.

The truth is, there’s no secret. You don’t get on people’s radar as a solid and sought-after coach until you’ve earned your stripes. It’s that simple.

For many, that reality is a tough pill to swallow. But rather than face the facts, the “About” sections on trainers’ websites become more and more fantastical.

All of a sudden, every young coach is “world-renowned,” “highly sought-after,” a prodigy who’s taking the industry by storm.

If you’re one of those trainers, I’m here to tell you that embellishing your resume can end up making you look worse, despite the initial objective of looking better. The following claims are the ones I see most often on social media bios, which means they’re also the least likely to fool anyone.

You Haven’t “Helped Thousands of People Reach Their Goals”

If you’re three years into your personal training career and you’ve already trained a thousand people, you’re either lying, or you have the worst client-retention skills in human history. Neither of those is a good look.

But let’s take the numbers seriously for a moment. How does anyone reach “thousands” of people? Do you add up every person who’s ever attended one of your group fitness classes? Every click on one of your blog posts? Every “like” on Twitter and Instagram?

I know it’s not like anyone’s going to fact-check you, but please have some integrity. There’s no shame in saying you’ve helped dozens of in-person and online clients, assuming even that much is true.

Post the actual numbers, or don’t mention them at all.

READ ALSO: “How to Build an Online Following from Scratch”

You Aren’t “The #1 Trainer in North America”

An arbitrary ranking or statistic in your bio, based on a lifestyle website’s clickbait article you may have lobbied to be included in, is a bright red flag to anyone with a functioning B.S. detector.

Even if it were possible to rank industry leaders in any legitimate way, that’s not the goal of those articles. It’s to get publicity-hungry trainers like you to link to the article and drive up the site’s pageviews.

They don’t care if you’re still waiting for the ink to dry on your freshly printed certification. But you should. Echoing such an unsubstantiated and unearned accolade gives your peers a very good reason to write you off.

You Don’t “Train Professional Athletes and Celebrities”

If you have a high-profile client, and the client consents, it’s completely legit to let people know. But working with one athlete, singer, or actor for five sessions doesn’t make you a sports-performance coach or a celebrity trainer.

That goes double if the athlete is a guy who plays right field for the Chattanooga Meerkats, or the celebrity was on season three of The Real Housewives of Muncie, Indiana.

Just to be clear, if those are your clients, there’s nothing to be ashamed of, or that you shouldn’t mention in your social media—again, as long as they’re on board with it. They might be the most interesting and colorful clients you have, and give you lots of material for articles and status updates.

What they aren’t is your golden ticket to a life that’s more glamorous than the one you have now, or a license to pretend you’re something you aren’t.

READ ALSO: “How to Train the Modern Celebrity”

You Haven’t “Been a Competitive Athlete for 20 Years”

Nothing is funnier to me than a 24-year-old coach who boasts of his decades (plural!) of experience as a competitive athlete.

In what other field would a professional CV include tee-ball, peewee hockey, or the chaos that ensues when preschoolers play soccer? It would be like an aspiring model claiming a decade of experience because of the bathroom selfies she’s posted on social media since 2008.

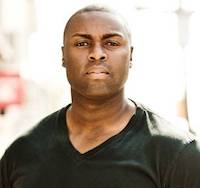

This isn’t hard. If you’ve loved sports since childhood, there’s nothing wrong with mentioning it. And if you played sports at a high level, just tell people what you did. For example, in college, I competed in track as a sprinter and long jumper. Here’s how I describe it in my bio:

I also ran track at the National level in university as a sprinter and long jumper.

See?

READ ALSO: “Five Lessons from 10 Years of Personal Training”

It’s Okay to Still Be Learning

I understand why young trainers feel pressure to exaggerate their credentials (although there’s no excuse for making stuff up). You’re entering a field where the average personal trainer is 40 years old, with 13 years’ experience. NCAA strength and conditioning coaches are five years younger, on average, but there’s a higher bar for getting a job like that. (Almost three-quarters have a master’s degree, for example.)

If you’re in your early to mid 20s, you’ve got a long way to go to accumulate the average experience of a personal trainer. You’re even farther away from the people who drive our industry forward and make it lucrative. But that’s no different from any other career path that doesn’t involve singing, acting, playing sports, modeling clothes, or taking them off.

Beyond a small percentage of outliers, status and respect have to be earned the old-fashioned way: with actual accomplishments, the kind that bring you loyal clients and long-term followers.

Those accomplishments come from being a disciple of the craft. From taking the time to develop your skills. From admitting you don’t have all the answers, but you’re willing to learn.

That’s how you earn admiration from your peers. And when you have that, you won’t need to boast about fantastic accomplishments, much less make them up. Others will do it for you.

Respect the game, and it will respect you in return.