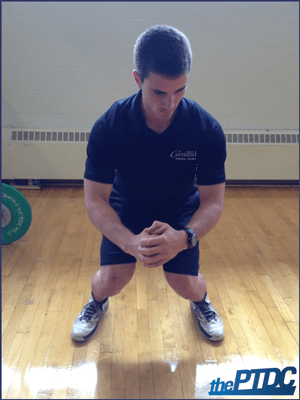

The squat is a staple in personal training programs. A textbook squat involves knee and hip flexion on the eccentric portion until the thigh is parallel with the ground followed by hip and knee extension.

However, during the body weight squat many common errors can occur:

- Heels coming off the ground and knees coming too far forward

- Knees caving in and foot pronation

- Leaning too far forward

- Lumbar flexion

When trying to address these issues, you must first understand that movement deviation from an ideal can happen for a number of reasons such as lack of experience, muscle weakness, muscle imbalances, and the client's structure.

It's also important to consider that different people move differently, and the same people move differently on different occasions. Although it's not easily definable, there's a range of acceptable exercise form -- as my friend and fellow strength coach Tony Gentilcore puts it, between "eye's bleeding and dead sexy."

Let's look at each of the issues typically seen during the body weight squat.

**Note: I've included a video at the bottom of this article outlining all of the main points.**

Heels coming off the ground and knees coming too far forward

Having the heels come off the ground could be due to coaching, muscle weakness, and muscle imbalances:

- Coaching

If the heels are coming off the floor this probably means that the knees are coming too far forward and the client is exhausting their dorsiflexion range of motion. Try having the client focus on posterior hip displacement, limiting the forward translation of the knees. Using a box could help the client get used to pushing the hips back rather than simply flexing at the knees.

- Muscle imbalance and weakness

Clients that squat in this fashion may be quadriceps dominant, meaning the knee extensors will be doing more work than the hip extensors. Apart from cueing, the trainer may want to focus on developing the hip hinge pattern and eventually loading it with exercises like the Romanian deadlift.

Knees caving in

Valgus collapse or medial knee displacement is one of the most common problems in the squat and could happen for a number of different reasons. Knee valgus is thought to be the result of femoral adduction and internal rotation and tibial aduction and external rotation (Bell).

- Coaching

The first thing the trainer should do is instruct the client to not let the knees cave in. During the squat the toes should be pointed slightly out with the knees staying in line with the toes. If the client's knees are caving in, "knees out" is a good verbal cue as long as they don't go into varus.

The trainer can put their hands on the lateral part of the client's knees and instruct them to push their knees into the trainer's hands. A band can also be useful so the client has to resist the inward pull of the band.

- Muscle imbalance and weakness

When a client has limited dorsiflexion range of motion the feet may pronate or the knees may cave in (Kritz). The trainer could coach a more hip dominant squat to avoid this problem. Neuromuscular characteristics associated with knee valgus include decreased gluteal activation or strength, and increased hip-adductor activation (Padua).

A heel lift is often used to determine if the medial knee displacement is caused by lower leg imbalances or hip imbalances or weakness. It's hypothesized that if medial knee displacement is not present after the inclusion of the heel lift that the lower body musculature was causing the dysfunction. If the aberrant knee movement is still present after using a heel lift than it can be assumed that the hip musculature was causing the problem.

"Correction of MKD when using a 5.1-cm (2-inch) heel lift is theorized to occur by increasing ankle plantarflexion and thereby decrease the tension within the lateral ankle musculature and restore the normal length-tension relationship of the medial gastrocnemius, anterior tibialis, and posterior tibialis so that they may better control knee valgus and foot pronation" (Bell).

Leaning too far forward

During the squat the client may start to lean too far forward. There's going to be a forward lean in the squat; most people won't stay completely upright. However, when the client is leaning so far forward that they face the ground, making the exercise look more like a good morning, it must be addressed.

- Coaching

There are several cues the trainer can give the client. For example, having them hold a weight in front of their body helps to serve as feedback to stay more upright. If the client leans forward they'll have to drop the weight or at least feel it pulling their torso forward. Another thing the trainer can do is put the client close to a wall and have them squat, instructing them to avoid hitting the wall. If these cues don't work start looking at what else may be causing this issue.

- Muscle imbalance and weakness

Potentially overactive muscles would include the soleus, gastrocnemius, and hip flexors whereas underactive muscles may include the tibialis anterior, tibialis posterior, and erector spinae (Hirth). Also, if the ankle joint is restricted the client may begin to lean forward more (Fry). This is seen in novice squatters. However, the client can be coached to stay upright even with restricted ankle movement. A box is particularly useful for this as well.

Lumbar Flexion

Lumbar flexion before reaching parallel is another common issue in the body weight squat. It has been postulated that if the client lacks hip mobility the lumbar spine will flex to compensate for the lack of range of motion (Kritz).

- Coaching

The trainer can use a high box squat to identify the point where form breaks down. If form breaks down on a 17-inch box work with the available range of motion while grooving the pattern, work down to a 16-inch box and then work towards having the client hit parallel.

Lumbar flexion may also be caused by a lack of ankle mobility. As mentioned earlier, if ankle range of motion is restricted the client may lean forward to compensate. Try adding a heel lift to allow the knees to come forward more. The squatting in front of a wall cue also applies, as it helps the client stay more upright. The trainer can also try front loading the squat with a dumbbell or kettlebell to increase anterior core activation.

- Muscle imbalance and weakness

Besides lack of hip mobility, anecdotal evidence suggests that lumbar flexion may also be caused by shortened hamstrings or a lack of core strength. The squat pattern shouldn't be loaded if the trainer observes that the client has the inability to squat without flexing at their lumbar spine.

The squat is a complex multijoint exercise that's used in most strength training programs. Before loading the pattern it is important to identify any major deviations in the pattern that could cause injury or impede performance when weight is added. More often than not, problems with the squat can be addressed by good coaching and cueing. Muscle weakness could also cause a problem with the pattern, and in some cases muscles may be overactive which could also cause a problem.

Here is a video on screening the squat that covers everything presented in this article:

Further Reading

Build Better Personal Training Programs - Greg Nuckols

Cues for Personal Trainers - Jarred English

15 Common Mobility Mistakes - Eric Cressey

The Art of Cueing (Not the Science) - Jonathan Goodman

References

- Bell D. R., Padua D. A., Clark M. A. Muscle strength and flexibility characteristics of people displaying excessive medial knee displacement. Arch Phys. Med. Rehabil. 89: 1323-1328, 2008

- Fry AC, Smith CJ, and Schilling BK. Effect of knee position on hip and knee torques during the barbell squat. J Strength Cond Res 17: 629-633, 2003.

- Hirth CJ. Clinical movement analysis to identify muscle imbalances and guide exercise. Athl Ther Today 12: 10-14, 2007.

- Kritz M., Cronin J., Hume P. The bodyweight squat: A movement screen for the squat pattern. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 31: 76-85, 2009

- Padua D. A., Bell D. R., Clark M. A. Neuromuscular characteristics of individuals displaying excessive medial knee displacement. Journal of Athletic Training. 47 (5) 525-536