Do your clients have excellent posture?

If they sit in front of a computer all day, commute long distances, or spend lots of time texting or watching TV, they probably don’t.

Many of them will display upper crossed syndrome, a postural compensation first identified and described by Vladimir Janda, the Czech physician who revolutionized rehabilitation therapy. It’s caused by sitting in a slumped position with your head tilted forward. (We understand that some therapists and rehab professionals challenge the validity of Janda's syndromes. We hope we've addressed the issue with appropriate nuance.)

The result is short, tight muscles on the front of your body and long, weak muscles on your upper back. It’s often accompanied by headaches or chronic back pain, shoulder pain, or neck pain.

Even if a client with upper crossed syndrome doesn’t experience pain, their poor posture can cause muscle imbalances, and the resulting compensations can compromise exercise technique. If uncorrected, it can also lead to painful trigger points or even injuries. Chronic depression of the sternum might even make it more difficult to breathe.

All that’s on top of the aesthetic cost of UCS. It makes the chest look smaller and the shoulders narrower. Your upper back develops a hunch, and the entire body appears less athletic.

Let’s talk about UCS—what it is, how to test for it, and how to correct it.

- What is upper crossed syndrome?

- What causes upper crossed syndrome?

- How to test for upper crossed syndrome

- How to fix upper crossed syndrome

- Upper crossed syndrome exercises

What is upper crossed syndrome?

We’ll start with a simple fact: The human head is huge. It weighs 10 pounds, on average.

No, it doesn’t sound like much—even your least conditioned clients can probably do something with a 10-pound dumbbell—until you consider its support system. The neck isn’t a dumbbell rack. It’s designed to rotate 40 degrees in each direction while also bending far enough backward and forward for you to scan the skies or search the ground.

What it’s not designed to do is support a 10-pound mass of brain and bone that’s leaning forward for much of the day. For your neck to work, your head needs to stay directly over the midline of your body most of the time.

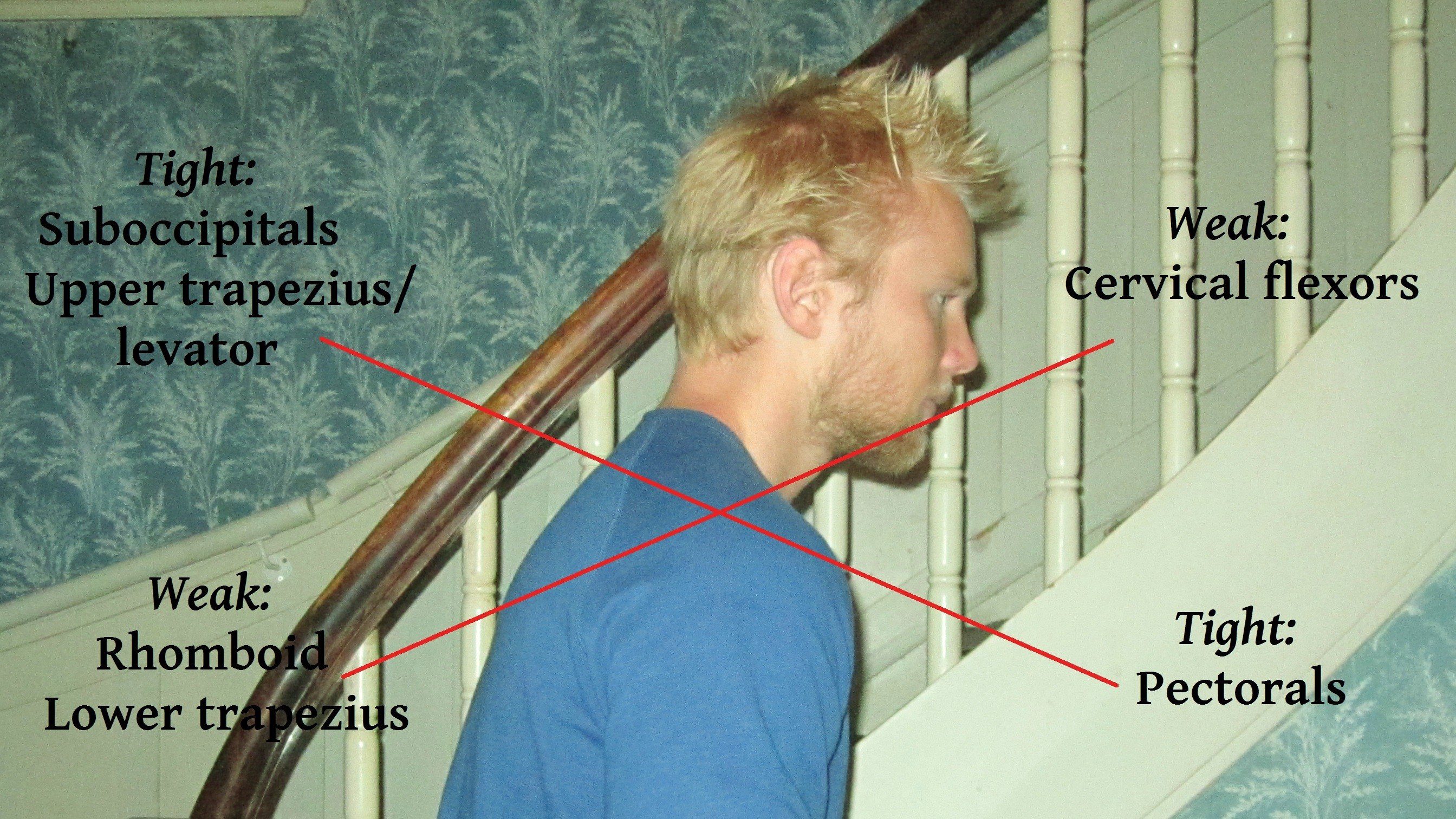

What muscles are affected by upper crossed syndrome?

As the head bends forward, these muscles become stretched and/or tight:

- Suboccipitals

- Upper trapezius

- Levator scapulae

The pectorals become correspondingly short and tight.

Meanwhile, the deep cervical flexors—small, stabilizing muscles on the front and sides of the neck—become weak. Their role is to pull your head forward, but if your head is leaning forward anyway, there’s not much for them to do.

Completing the cross are the rhomboids, serratus anterior, and lower trapezius, all of which become stretched and/or weak.

Muscles affected by upper crossed syndrome

READ ALSO: Anterior Pelvic Tilt: What It Is, and How to Fix It

What causes upper crossed syndrome?

Upper crossed syndrome can result from any or all of these three factors.

Sedentary lifestyle with forward head posture

Personal trainers spend most of our time on our feet, but the people we train spend most of their time sitting. It’s not entirely their fault. The work that allows them to pay us usually involves long hours in meetings or in front of a computer, often combined with long commutes and frequent travel.

Before, during, and after those sedentary events, they’re probably texting or reading something on their phones.

And they do all of it with their heads leaning forward and upper back hunched, creating or reinforcing upper crossed syndrome.

Unbalanced training

Picture a 20-year-old guy who trains his pecs and delts three times a week with bench presses, flies, and lateral raises; does push-ups almost every day; and rarely trains his upper back.

Or a 40-year-old cyclist who spends hours a week on a bike, all of it with her upper back rounded.

Or a 50-year-old former athlete who spends half of each workout on his core, doing hundreds of crunches with his hands pulling his head forward.

Poor exercise technique

All the examples of unbalanced training are exacerbated by doing those exercises with suboptimal technique.

The crunch is the most obvious example, but if you look around the gym, you see it everywhere. Whether it’s a plank or a TRX row, the neck is rarely aligned with the torso and lower body.

The vicious cycle

These three problems—forward head position, unbalanced training, and/or poor exercise technique—both promote and worsen upper crossed syndrome, which makes it harder to sit with good posture or exercise with good form.

How to test for upper crossed syndrome

Physical therapist Chad Waterbury, DPT, recommends a simple visual assessment for UCS. Ask your client if you can take a photo of him standing sideways. But don’t tell him why. As soon as he hears the word “posture,” he’ll stand up straighter.

Have him stand sideways to a bare wall in socks or bare feet, with his heels together. Ideally, he’ll let you take the picture of him without a shirt. For a female client, ask if you can take the picture in a sports bra. (Obviously, you’ll need to do this out of public view.)

After you take the photo, use an app to draw a straight, vertical from the bottom of the fibula on the outside of the foot to the top of the head. (Waterbury uses Hudl, a free app for Apple devices. Other options include the $40 Posture Analysis app, which is used by a lot of clinicians.)

Ideally, that straight line should intersect with the knee, hip, deltoid, and ear. If the ear and the middle of the deltoid are forward of the line, it’s a telltale sign of UCS.

How to fix upper crossed syndrome

1. Set the shoulders and tuck the chin

A person with UCS looks like his body has reshaped itself to accommodate walking around with his hands in his front pockets, usually with his head down, as if he’s trying to avoid eye contact.

But what happens if you ask him to put his hands in his back pockets? His posture changes: His shoulder blades retract and his head comes up, like he’s suddenly gained confidence.

Setting the shoulders and tucking the chin is an exaggerated version of that. Tell your client to pull his shoulders back, and imagine he’s sticking his shoulder blades into his back pockets.

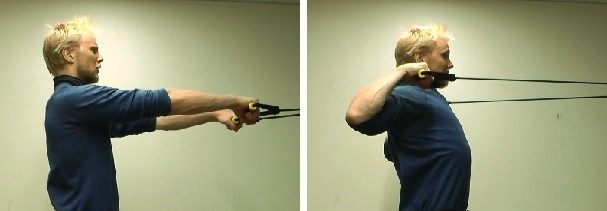

The chin tuck usually takes a little more coaching. As you can see in the photo on the right, you want him to make a double chin while keeping his neck in a neutral position.

Upper crossed syndrome uncorrected vs. set shoulders and tucked chin

If the client struggles to activate his deep neck flexor muscles, place a tennis ball under his chin. He’ll have to pull his shoulders back farther to hold it in place.

Some clients will need to work on this for a while before they get it. But get it they must, because it’s the first step to correcting UCS.

2. Upper crossed syndrome exercises

The next step is to perform corrective exercises. The goal is to get the client to retract the shoulder blades with added resistance. Seated rows and face pulls are especially effective.

Don’t go heavy in the beginning. Start with a band or light weights on a cable machine, and do multiple sets of 10 to 15 reps. Pause in the fully contracted position for one or two seconds. The pause not only helps her feel her muscles working, it slows down the movement to limit momentum.

Once the client masters the technique, you can have her train almost to failure, increasing the load each time she reaches the rep target. Just make sure she pulls her shoulders down and back on every repetition.

Face pull

Seated row

3. Stretch the tight chest muscles

Strengthening the back muscles is more important than stretching them. But since tight chest muscles are a component of UCS, I like to use some basic pectoral stretches. Encourage your clients to do this one at home on non-training days.

Pectoral stretch

4. Set the shoulders correctly when lifting

People with UCS generally struggle with technique in a wide range of exercises. It’s easy to understand why: With the shoulders rounded and pulled forward, it’s hard to get into position to lift correctly. Then, while they’re lifting, their range of motion limitations and muscle imbalances lead to compensation patterns.

Thus, it’s not enough to strengthen specific muscles with targeted exercises. You also need to help your clients transfer that improved muscle function to the other exercises in your program.

Some quick tips for the big three:

Bench press

Set the shoulders down and back. Keep the rear delts locked in throughout the lift.

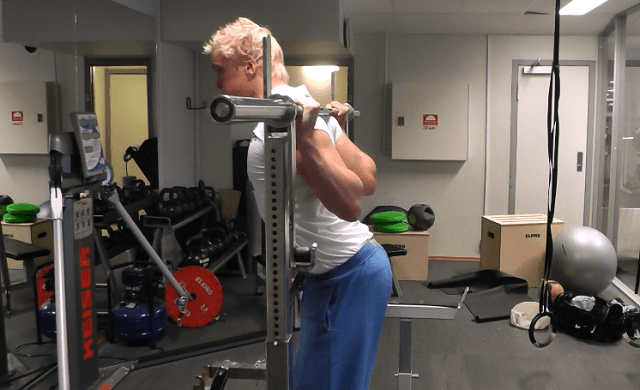

Squat

The barbell back squat probably wouldn’t be your first choice for most of your clients. Goblet squats are easier for them to learn, and allow them to perform the movement pattern with decent technique and sufficient depth.

But for clients with upper crossed syndrome, a barbell on the back can help them get and keep their shoulder blades back and down. It also helps them get the chest high.

Barbell squat with full scapular retraction

Deadlift

The deadlift is a tough one for clients with upper crossed syndrome because they need to follow two cues that will feel unnatural at first:

- Shoulder blades back and down

- Chest up

The best variation depends on the client. This kettlebell deadlift from Dean Somerset allows your client to keep his shoulder blades locked in place throughout the movement.

READ ALSO: Troubleshooting the Deadlift

Sets and reps

The more technically or cognitively complex an exercise is for your client, the less volume you want.

The squats and deadlifts, in particular, will work best with two or three sets and single-digit reps. When you’re asking your client to focus so much on such crucial details, more reps mean diminishing returns.

Conversely, as mentioned earlier, you can use higher volume on rows and face pulls. You’re only asking your client to concentrate on one important detail—retracting the shoulder blades—which is relatively simple to learn and maintain.

The bench press is somewhere in the middle. You can program as many reps as your client can do with his shoulder blades locked down. But keep in mind that it’s far from the most important movement pattern for someone whose chest muscles are already tight.

5. Pay attention to posture and regularly perform mobility drills

No matter how thoroughly and effectively you address upper crossed syndrome in your workouts, never forget that your clients spend most of their time outside the gym. And when they aren’t training with you, they’re doing all the things that produced UCS in the first place.

But just because you can’t supervise them during those hours doesn’t mean they can’t follow your instructions. Help them find a way to pay more attention to their sitting and standing posture, and to remind themselves to do simple exercises like the chest stretch I showed earlier.

You can also give them a band or rope to keep nearby, and use it for exercises like this shoulder mobility drill.

Mobility drill for shoulders

Final thoughts about upper crossed syndrome

You can’t expect a client who’s spent many years developing UCS to change her posture and behaviors overnight. It’s a long process.

Focus on the small wins: stronger upper-back muscles, improved form on key exercises, better mobility and movement quality, and less pain or discomfort, if that was an issue for your client when she first hired you.

READ ALSO: The One Thing You Haven’t Considered About Healthy Shoulders

READ ALSO: Why You Must Not Stretch Hypermobile Clients

If You’re an Online Trainer, or Want to Be …

You can’t move forward in your career until you learn how to coach fitness and nutrition online responsibly, effectively, efficiently, and confidently.

If you’d like to get ahead, and stay ahead, consider enrolling in the Online Trainer Academy Level 1 Certification.

(Or if you’re already training clients online, making more than $1,000 a month, and looking for a more scalable business model, you may be a better fit for the Online Trainer Academy Level 2.)