You may have to squat differently than someone next to you. This should be common sense, considering the diversity of the population. If you had all your clients try to perform a squat, there would be those who smash depth and those who struggle to bend past 90 degrees.

What determines our range of motion? Training history? Time spent under the bar? Tissue health? Those things absolutely play a role, but they don't ultimately determine how much mobility we have and can use.

We know joints deteriorate with age, and those deteriorations cause reductions in range of motion. But I once had a 72-year-old client who could still squat hamstrings to calves, while his group training partner had to warm up for 10 minutes just to hit 90 degrees. Women tend to have better overall mobility than men, but some struggle to control their positions without tipping over.

A common setup for a movement like a deadlift involves keeping everything relatively square: both feet pointed forward, shins equally close to the bar, knees vertical over feet. This has been taught as the way to limit imbalances, but in complete honesty may be causing more imbalances than it's solving. It assumes symmetric structure, which as I'll show isn't always the case.

How anatomical variations determine range of motion

Walk into a random high school classroom and you'll see huge differences in physical size and shape. Even within a single family, siblings could display a variety of heights, weights, and limb lengths.

That's just what you can observe from the outside. Our joints also have anatomical variations in shape, alignment, positioning, and relative angles of attachment of specific bones and joints, all of which help determine how far and how well those joints can move.

One basic tenet that applies to everyone: You can't stretch bone into bone without something going wrong. When your joints run out of room, you can't get more range of motion without causing some trauma to the joint, or causing neighboring joints to increase their movement to accommodate. The shape and position of your joints dictate when and where you develop that bone-to-bone contact.

Let's focus on the hip for this discussion, since that's where we have the most research on positional and anatomical variances.

READ ALSO: The Real Reason Why People Must Squat Differently

Anatomy of the hip joint

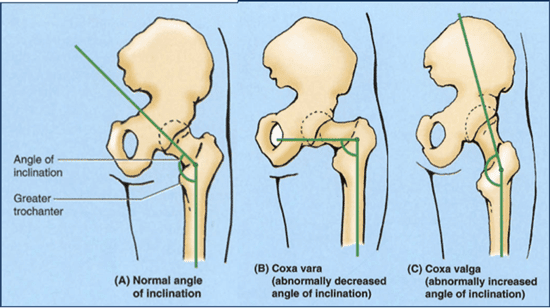

The femoral neck angle is the most common individual difference. It's usually classified in one of these three categories: coxa valga (a more vertical angle inserting into the pelvis), coxa vara (a more horizontal angle inserting into the pelvis), and what's considered a more "normal" angle of roughly 40 to 50 degrees. The funny thing is, if you add up all the people with coxa vara and valga, you'll see more of them than you will people with the "normal" femoral neck angle.

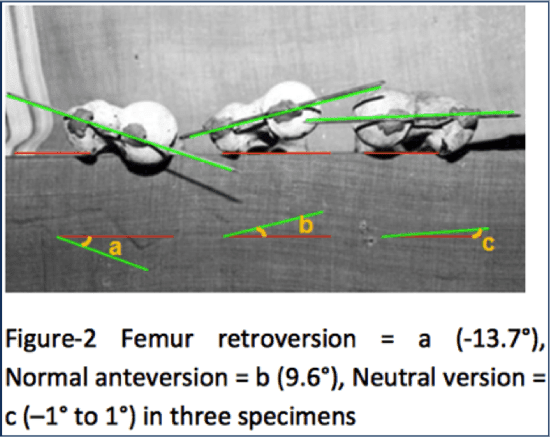

You can also have a neck that's angled forward, a position known as anteversion, or angled backward, which is called retroversion.

Zalawadia et al (2010) showed variances in femoral neck angles of as much as 24 degrees between samples, and even showed a significant difference between the left and right hips of the same individual. Those factors can mean huge differences in optimal form and range of motion from one client to the next.

A client with a femoral retroversion will probably have bone-to-bone contact sooner in a squat than someone who has more of an anteversion alignment. The difference in hip flexion could be 20 degrees or more. When you consider that a full squat could be anywhere from 140 to 160 degrees of hip flexion, with parallel occurring around 110 to 120 degrees, 20 degrees is a massive difference.

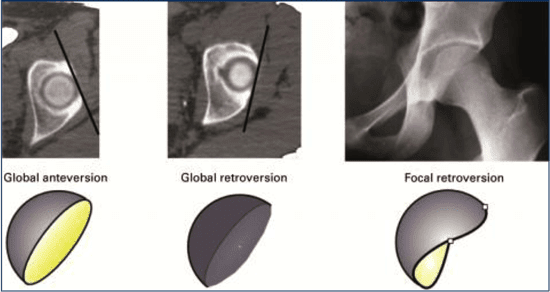

The alignment of the acetabulum, the hip socket, also affects squat form and range of motion.

Like the femur, the acetabulum can be in anteversion or retroversion. Two clients could have identical hip sockets in terms of size and shape, but their alignment could differ by more than 30 degrees. The one with the most anteverted acetabulum could have 30 extra degrees of hip flexion, while the one with the most retroversion would have 30 degrees more hip extension.

The shape of the hip socket can also be very different, as Fern and Norton showed.

Those with the C-shaped socket (focal retroversion) would have a massive advantage in range of motion.

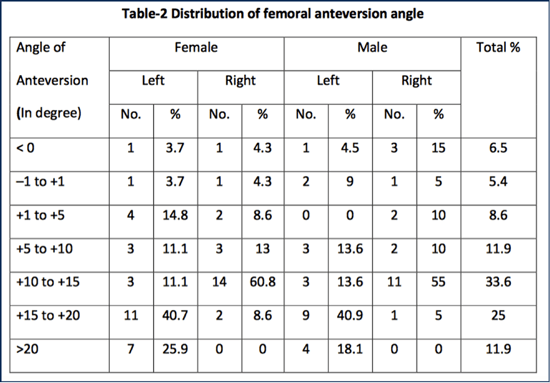

Finally, there's a true wild card: The same client might have more than 20 degrees' worth of difference in hip alignment and positioning. A symmetrical setup—both feet parallel, or turned out at the exact same angle—would be a mistake for that client.

Look at the bottom row. A quarter of the female study subjects had more than 20 degrees of anteversion in their left legs, but not a single one on the right side. Three-fifths showed 10 to 15 degrees on the right side, but just 11 percent hit this range on the left. More subjects showed less anteversion in the right leg than in the left, and the difference wasn't consistent between the actual degree of anteversion. Every hip was different.

The same could be said for men, where the majority of left leg samples had greater than 15 degrees of anteversion, while a plurality of right leg samples were between 5 and 15 degrees. A 10-degree difference in range of motion from one hip to another is substantial.

READ ALSO: The Best Exercises for Training the Hip Hinge

Bad things happen when you ignore hip asymmetry

There are those who will discard this information and continue to say everyone should squat deeply—"ass to grass," as the poet said.

To that I would say, if they can squat like that, train hard and take advantage of it.

But if they don't have the hips for it, they'll almost certainly pay a price for training outside their anatomical limits.

In significant cases of femoroacetabular impingement, repeated compression of bone into bone causes a bone spur to form, which further limits range of motion. The only way to get rid of it is with surgical removal, and even then you have to hope the labrum isn't damaged.

Fabricant et al (2015) showed that 37 percent of asymptomatic individuals had clinically significant markers of impingement-related changes in their hip structure. That number jumped to 54.8 percent in athletes.

The shape of your hip sockets also affects your risk of sacroiliac (SI) joint pain. Morgan et al showed that 47 percent of people with a history of SI joint pain had what would be classified as deep hip sockets, and 33 percent had impingements.

READ ALSO: Should Personal Trainers Stretch Their Clients?

Three tests to find the best squat stance

From my experience with my own training and working with my clients, I've found that those with more anteversion typically have no problems squatting to depth. Those who're more retroverted are likely to struggle with depth, but they rock out with extension. People with more lateral positioning of the acetabulum tend to require a wider stance, and struggle mightily with their feet closer together.

If one hip is more anteverted and one is more retroverted, that client may need to squat with a slightly rotated stance, with one foot (usually the right) turned out slightly more than the other.

Which brings us to the most important question: Assuming you don't have radiographic images of your clients' hip architecture, how in the world do you use this information in your training?

Fortunately, you can answer that question with these simple assessments.

Supported squat assessment

This is a simple way to determine the client's best squat depth. Have the client grab a solid, stable object for support, and position them so you can see observe their hips and lower back. Have them squat down as low as possible while using the using the support for balance. You're looking for the position where they're as deep as possible. When they get to a point where their back rounds, that's their end range of motion for hip flexion. Going farther produces the dreaded butt wink.

While at the bottom, have them open their feet to a slightly wider position to see if they can get lower. Then have them turn one foot out and in and see what happens. Finally, narrow the stance and repeat.

Choose the position that gives your client the best depth without lumbar flexion or pain in the front of the hip.

Once they're in their deepest squat, have them let go of the support and stand up without assistance. Repeat, using the support on the descent but rising without assistance. Now have them descend into the squat without assistance. The movement should feel easy and fluid, without obvious strain or tightness.

Hip extension assessment

Have the client on their back with bent knees, and drive their hips up without arching their low back. See how much extension they can get. Most people will get to neutral, or a few degrees beyond. Some people can get incredibly far into extension, as judged by the line from the middle of the thigh through the torso. A straight line denotes neutral. A slightly flexed position is a negative angle of extension, and if the hips rise above the torso, that's a positive extension angle.

For individuals who lack extension to reach or go past neutral, they'll obviously have a short range of motion on hip thrusts. They'll also struggle to develop anything close to a good kick in sprinting.

Lateral hip mobility assessment

Finally, you'll use the goalie squat to test the lateral capability of the hip joint in a somewhat passive manner. On hands and knees, have the client open their knees as wide as they can without ripping their hips apart. When they get as wide as possible, have them try to sit back without rounding the lower back.

This gives you an idea of how wide you could theoretically make your stance during a squat or deadlift. It may not be the best position for squat depth, but it does show you the outside edge of your lateral mobility. If your hips barely form a 90-degree angle, you won't be able to do squats or sumo deadlifts with a wide stance. And if you try, it'll be uncomfortable at best, and injurious at worst.

These three tests will give you a lot of information:

- What position gives you the best squat depth

- How much hip extension you can achieve

- How much lateral mobility you have

From this you can determine whether you have a lot of mobility or a specific directional limitation, or if you're built more like the Tin Woodman from The Wizard of Oz. (Good luck finding that oil can.)

Let's break down a couple of scenarios and see what positions would be best for your clients.

Low flexion, low extension, low lateral movement

A client who hits this trifecta is the Tim Woodman, basically. Because they'll never achieve much depth, higher squats to a box are a good choice. Likewise, deadlifting from the floor is probably a bad idea. Try pulling from a rack or blocks, having the client use a modified sumo stance to prevent low back involvement.

On the bright side, this client will probably be good at exercises they can do in an upright position, like loaded carries.

Good flexion, low extension, low lateral movement

This client can squat well, but split-stance exercises will be a challenge because their low back will try to do all the work. A shoulder-width squat stance should work best; going much wider will probably cause some lateral hip discomfort.

Conventional deadlifts should be a better fit than sumo, and with good coaching the client should be able to pull from the floor.

Good flexion, low extension, high lateral movement

Cherish this client, because they can squat well with a wide or narrow stance, or anything in between. Their lateral mobility makes them look like a ninja at times.

Low flexion, low extension, high lateral movement

This client needs a country mile between their feet. The more real estate in the middle, for both squats and deadlifts, the better.

High flexion, high extension, high lateral movement

If this client hasn't at least auditioned for Cirque du Soleil, they've missed their calling. We're talking about freakish mobility. They can do pretty much do any squat or deadlift variation. The real risk is tendinitis as their muscles try to make up for the stability they don't get from their shallow hip sockets.

Final thoughts about optimal squat stance

If you take nothing else away from this article, I want you to remember this:

There is no right or wrong squat stance. It's okay if the client barely reaches 90 degrees of hip flexion, or squats diaper-to-heels like a toddler, or anything in between.

The only thing that matters is what's best for the client. The worst stance is the one your client isn't anatomically suited for. The best stance is the one that allows the client to make the most progress with the least risk.