If you were to eavesdrop on conversations between people who take pride in their physical activity, you'd probably hear some common themes:

"I'm doing intermittent fasting."

"Really? I'm going paleo."

"My trainer has me on this really hard workout he got from JillianMichaels.com. It's gotta work since it's so hard."

"My shoulder's been hurting for the past few years, but I think I could probably train through it and it will go away on its own."

"I want to run faster, so I'm going to double my mileage this week."

You also might encounter a few who complain of chronically tight hip flexors. No matter how often they do hip flexor stretches, or how much time they hold each stretch, the muscles remain tight and unforgiving. They simply refuse to loosen up.

The problem here is simple: If it's not working, it's probably not the right solution.

But before we talk hip flexor stretches, let's look at the hip flexors themselves.

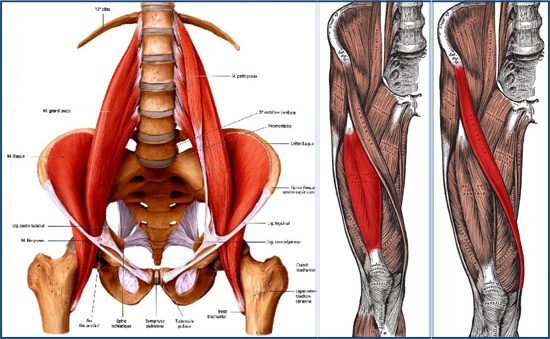

Hip flexor anatomy

These are the main components:

- Iliopsoas (the iliacus and psoas muscles)

- Sartorius

- Rectus femoris

The iliacus attaches on the upper portion of the femur and begins on the inside crest of the ilium (inside of the pelvis), where the psoas attaches all the way through the transverse processes of the lumbar spine, even binding into the discs directly. The rectus femoris begins at the base of the anterior superior iliac spine, and attaches all the way down to the knee cap, whereas the sartorius starts in the same place as the rectus femoris, but attaches on the medial aspect of the knee, blending with the MCL and portions of the hamstrings.

Here's what it all looks like. Click here or on the picture to see a larger version of this image. (Image source: Deansomerset.com)

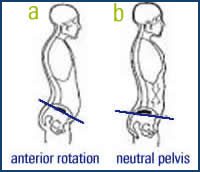

When these muscles contract together without the use of the floor, we see hip flexion, as in the case of a hanging leg raise. When we see the muscles contract while the feet are contacting the ground, we see a variation of hip flexion known as anterior pelvic tilt.

Source: deansomerset.com

READ ALSO: What Is Anterior Pelvic Tilt, and How Do I Fix It?

The iliopsoas has an underrated role in spinal stabilization. It makes sense when you see how the psoas attaches all along the lumbar spine, providing compression and stabilization against uncontrolled spinal flexion, lateral flexion, and shear. It's kind of a big deal like that.

Interestingly enough, the psoas also has tremendously important fascial networks, with the medial arcuate ligament providing a continuation directly to the diaphragm. Its lower fibers directly attach to the pelvic floor. It's another reason why breathing patterns can affect everything.

Panjabi showed in Therapeutic Exercise for Spinal Segmental Stabilization that when the transverse abdominis isn't working well after a low back injury, the psoas kicks up hard to cover the difference. This simple feat shows how much of a role the psoas plays in spinal stability.

So for people who have chronically tight hip flexors, which would be the more effective solution: stretching them, or addressing the fact that they're pulling double duty for an unstable spine and underdeveloped core, which is what made them tight in the first place?

Another way to look at it:

If you stretched a short and tight muscle and it regained length, it shouldn't get tight again, should it? Conversely, if the muscle wasn't technically "tight," but rather holding excessive tone in order to keep your spine from looking like a losing round of Jenga, stretching it will just give more opportunity for low back pain, and quickly lead to the muscle tensing up again to defend the spine.

That's the problem with conventional hip flexor stretches.

So is the hip flexor tight because it's short, or because it's responding to a weak core?

Simply put, it's typically a core dysfunction. But a weak core isn't simply an inability to do crunches and stuff like that. It's the inability of the spine to maintain a stable and powerful foundation in a neutral pelvic position, with fantastically awesome glute activation to drive the body forward.

One way to effectively "stretch" the hip flexors is to get the pelvis back to neutral, or even into a posterior tilt, while firing the living hell out of your glutes. I'm not simply talking about maximal voluntary contraction. I'm talking cracking walnuts with your cheeks. The kind of pressure that turns a ton of coal turn into three carats of diamonds.

We can do this in a half-kneeling position with a postural isometric hold ...

... or by making someone hate their entire existence through a rear-foot-elevated split squat focusing on vertical spine and pelvic tilt. (Now that's a hip flexor stretch!)

These tend to make people unable to walk for a few minutes after completing them, especially when they get into the right position where those hip flexors (specifically the rectus femoris) stretch to their limits under load.

If stretching these suckers out doesn't produce the desired lengthening of the hip flexors, we can work on getting the core stiff and stable, with the goal of removing the need for the iliopsoas to provide spinal stabilization.

We can plank the hell out of that sucker as long as we keep a neutral pelvis and spinal position.

In addition to planks, you can use anti-extension, -flexion, and -rotation exercises, which train the body to resist external challenges to core stability.

You'll finish with hip extension movements, during which the glutes act as an agonist to the hip flexors, and also provide low back stability. By helping the core muscles stabilize the spine, they reduce the impulse on the psoas, therefore reducing the "tightness."

Glute activation to combat hip flexor stiffness is best with full-range extension exercises like deadlifts and hip bridges. Resist the urge to use, and then drop, copious amounts of weight while making loud grunting noises. Yes, it signals to everyone how awesome your client is, but it's not the recommended way to relieve tight hip flexors.