Once you know where to look, you'll find that most clients present with an alignment issue in their pelvis that can cause a series of dysfunctions both up and down their kinetic chains. It's called anterior pelvic tilt, and when excessive, it can cause pain, diminished performance, or both. The good news: You can fix anterior pelvic tilt, and get your clients on the path to better quality movement.

Pelvic tilt can occur in the anterior or posterior direction. The more common anterior pelvic tilt (APT) is the forward rotation of the pelvis that pushes the butt out and arches the lumbar spine. It doesn’t matter who your client is: a desk jockey or a great squatter can show anterior pelvic tilt.

Ideally, we’d like the pelvis to be as “normal” as possible, but most people don’t even know what an aligned pelvis feels like. Further, clients with APT aren’t necessarily aware of the many issues related to this forward rotation in their pelvic girdle. Their hips might feel fine, but they may present with pain in their lumbar spine.

As trainers, we should know that oftentimes the source of a problem is not in the same location as the pain.

(To discover how to quickly assess and correct movement restrictions, download our FREE Movement Screening Guide.)

What exactly is anterior pelvic tilt, and why is it bad?

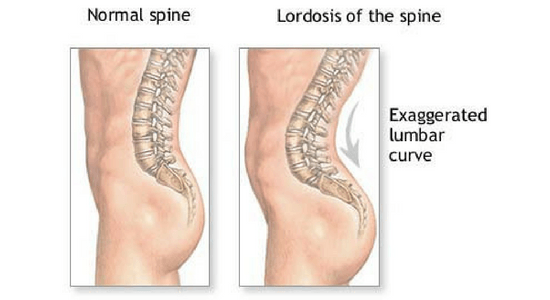

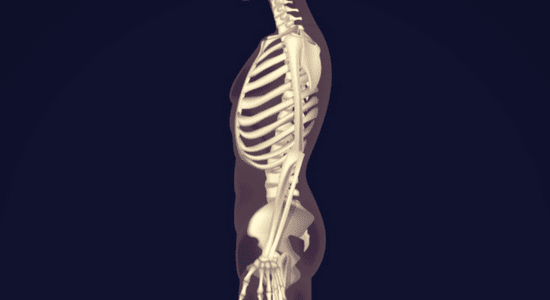

Before we can fix anterior pelvic tilt, it’s important to understand what APT is and how it is typically manifested. The pelvic girdle and the many muscles that surround it are in some way involved in every single movement performed in the gym. Anatomically, anterior pelvic tilt is a forward rotation of the pelvis, causing the forward portion of the iliac to move inferior (or lower) to the back. This pelvic tilt pulls the lumbar spine into lordosis, making it look like the client is essentially pushing his ass out.

This position pulls the abdominal muscles into a stretched position, which over time leads to a drastically weakened anterior core, specifically the transverse abdominals and the internal and external oblique slings. That’s not all: the glutes and hamstrings also suffer from being stretched for long periods of time. Lacking appropriate intramuscular tension within these muscle groups is both the cause and effect of anterior pelvic tilt.

Clearly, APT is a complex problem and commonly associated with low back pain. This is not surprising if you think about how the lower back extensors, or erector spinae, and the hip flexors need to contract heavily to support the rotated position of the pelvis and the lordosis, or inward curvature, in the lumbar spine. As a result, your clients feel discomfort not only in their lumbar spine, but also in their knees and ankles because they continue to exercise with poor form and have poor posture to begin with.

Anterior pelvic tilt is not simply “present” or “not present.”

As with most of anatomy and physiology, pelvic tilt is not an absolute position. It occurs on a spectrum, where there are varying degrees of pelvic tilt. Some can cause pain and impact performance, while others are subtle adaptations to life and training.

As I said before, you can fix anterior pelvic tilt, but the amount of time spent on each client heavily depends on his goals, current ability level, and the severity of the pelvic tilt. The solution is partly to program mobility movements that emphasize t-spine extension, a posterior pelvic tilt, and a neutral lower spine, self-myofascial release techniques, and appropriate stretching programs. All of these help restore freedom of movement in your clients with APT.

Some clients may possess only a mild amount of APT while standing, but have no up and down-chain effects of concern. In these cases, these clients may not require as much attention. Then there are clients who “live” in hyperlordosis. Whether they’re brushing their teeth, cooking dinner, or sitting on the couch, the pelvis is constantly rotated forward, and these are the clients who need work on improving posture.

To properly assess anterior pelvic tilt, ask yourself these questions.

You have to critically ask yourself why a client is in anterior pelvic tilt in the first place:

Is it a compensation or an imbalance? Or could it be a subconscious/conscious mechanism developed to become better at a task?

For clients who spend much of their time in a seated position, anterior pelvic tilt develops from inactivity, muscular imbalances, and poor neural control of their posture. It’s not like these clients know their tilt isn’t “normal” or that they’re at risk for negative effects though. So they don't even realize they should fix anterior pelvic tilt.

On the flip side, even avid lifters can present APT. That’s not surprising. Regularly loading squat, lunge, and hinge patterns require the active use of anterior pelvic tilt to create force and leverage. They’ve adapted to a mechanism that helps them perform at a higher level, but probably don’t know they’ve carried this habit to everyday postures. Most of these clients will see good results once they incorporate corrective measures to correct APT though.

While anterior pelvic tilt can be a literal pain in the behind, some people are still able to lift at the elite level and remain pain-free. For these rare folks, it is much better to leave a great thing great. Sure, you can add a few correctives here or there, or introduce new mobility or stability movements to their program, but don’t try to make wholesale changes to someone who doesn’t need them.

Make a client want to fix anterior pelvic tilt.

A client finds out he has anterior pelvic tilt, so what? You know it’s problematic, but the client probably does; or if he does, he doesn’t care. Here you can use this simple analogy:

Your pelvis is a bowl of water. It can pour water out of the front (anterior tilt) or the back (posterior tilt), or kept neutral (neutral).

This simple visual can help the average client understand the various positions the pelvis can achieve in the sagittal plane. When paired with quality training modalities, this understanding can quickly improve a client’s posture, as well as his cognitive awareness of changes in his body (especially as it pertains to poor posture). The client might feel some muscles stretch and others tighten when you go into a particular tilt pattern. This can be strong motivation to fix anterior pelvic tilt.

For the performance-conscious clients, emphasize that if they fix anterior pelvic tilt, they can become stronger. Point out that anterior pelvic tilt limits their effective range in the squat, hinge, or lunge pattern. By maximizing the range of motion in these patterns, especially under load, they can significantly increase force production, hypertrophy, and metabolic results. In other words, they’ll get strong as hell, and there aren’t any clients who don’t want to hear that.

(For more stories tailored specifically for fitness professionals, become a PTDC Insider. It’s FREE and you’ll get best fitness industry advice—from training techniques to coaching skills to marketing and business—delivered straight to your inbox every week. Sign up here.)

Fix anterior pelvic tilt with these 5 exercises.

Ultimately, a trainer’s goal is to coach a client with APT in the following ways:

1. Stretch and mobilize the lumbar spine, thoracic spine, and anterior hip.

2. Strengthen anterior core.

3. Strengthen glutes and hamstrings.

All of these goals can be achieved by creating a program that includes SMR, stretching, mobility, and strengthening movements. Your client does not need to abandon his current training routine to specifically correct APT. Rather, simply have your client supplement his or her training program with the following five movements to make a difference.

- RKC plank

Coaching a client out of APT requires a strong anterior core and improved glute strength, both of which the RKC plank helps with. The RKC plank is also known as the max-tension plank. It’s so effective that I believe it should really be the only version of a plank. Coach your client as follows:

* Keep feet together, squeezed as though the client is holding paper between their heels and toes.

* Contract the glutes by pretending they’re holding a credit card between those cheeks.

* Keep hands apart and pull in opposite directions to create tension in the lats.

* Pull the belly button toward the spine and draw the abdominals up and inward.

* Keep a neutral cervical spine and slide forward onto the tiptoes of your client’s shoes. Their nose should be out in front of their hands.

If done correctly, most struggle to maintain full tension beyond ten seconds. Have your client focus on the quality of the plank, not the length of time it is performed.

- Foot-Elevated Glute Bridge with Isometric Glute Hold

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uB_OanZw_Js

A glute bridge is a fundamental exercise to drive neural attention into the posterior chain. Raising a foot increases the effective range of motion and hamstring recruitment, and better simulates the full depth that is desired in a hinge pattern. For an added benefit, throw in a five to 10-second isometric contraction at the top of the movement to sufficiently exhaust the glutes.

* Keep the legs in line by not going too wide or narrow with foot position on the box.

* Drive should occur through the heels towards the midfoot, with an emphasis on “screwing” into the box.

* Arms should be out to the sides at a “T.”

* The abdominals should be contracted and drawn into the body to brace the spine.

* Movement should be 100 percent through the hips.

Start all clients on the floor and progress them to this version once they have repeatedly demonstrated the ability to maintain concentric and eccentric control of the bridge pattern, without arching their lower spine. Not all clients, especially those with lower back injuries or those who are new to exercise, are ready for propping their feet onto a box.

Remember, the goal is not to get a client to bridge as high as they can, but to effectively control all elements of the movement with their pelvis.

- Low to High Pallof Press

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iq0KJ2KVVaQ

The Pallof press is commonly used as an anti-rotation exercise to challenge a client’s core stability. In this instance, it is still doing that with a bit of extra challenge.

Perform a standard Pallof press from a half-kneeling, dual-kneeling, or standing position. Once the client has pressed the cable handle out in front of him, coach him to lower the cable toward his belly button and then raise it to just above his head. This progression of low to high trains elements of anti-flexion and anti-extension, which effectively target the transverse abdominal and internal obliques.

* Coach active bracing of the core and a two-second movement tempo for all parts of the pattern.

* Maintain a manageable range of motion for the high/low movement. It should be under control at all times.

* Start lighter in terms of resistance and progress in repetitions prior to adding more load. Once a client can do 12-15 repetitions with absolute control, then add a plate.

* Observe the balance between the two points of contact with the floor. Most clients will shift their hips to accommodate the lateral load.

This variation of the Pallof press will strengthen the core musculature to improve performance on compound movements and in life.

- Handcuffed Kneeling Kettlebell Hinge

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0FAN1WhHfk

I learned this from attending a workshop hosted by Todd Bumgardner, and since then, I have been using this movement with nearly every client, regardless of ability level, to help with hinge patterns. It is effective as a prep movement or as an intra-set corrective.

* Using a mat or Airex pad to cushion a client’s knees, place the client in a dual-kneeling position.

* After placing an appropriate kettlebell between his feet, have the client “sit down” and grab the bell with his hands, which are located behind his back.

* Once he has the bell, cue “get tall” and hold the kettlebell behind his butt as though he were in handcuffs.

* Instruct him to stay tall and tight and push his butt into the bell until he can’t go any further.

This exercise allows your client to groove the hinge pattern over and over again while minimizing risk of load. It also eliminates a myriad of other factors that distracts from how to rotate his pelvis completely. A great set goes from posterior tilt to anterior tilt and back again.

- Anti-APT Mobility Triad

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vrqXJXwxJo

Also known as Half-Kneeling Couch Stretch to Pigeon Pose to World’s Greatest (but try saying that to your client).

Not everything needs to be strengthened in order to fix anterior pelvic tilt. A mobility trio like this one can effectively address muscle tightness. It helps to remove unneeded tension to allow for the skeletal system to better go from position to position, which in time, can lead to improved posture.

Watch the video above to see what the three movements that help fix anterior pelvic tilt look like, as well as how to logically flow from one to the next.

* No stretch should be held longer than five seconds, as the goal is to mobilize and increase blood flow, not create extensive pull on the muscles.

* Repeat the flow three to five times to maximize your client’s mobility.

* Emphasize the fluidity between movements and “slide” into your client’s end ranges. Don’t let your client bump and grind their way through this.

* For the World’s Greatest: Have your client focus on breathing into his expanded rib cage and find a point of relaxation and release.

* For the Pigeon Pose: Think of trying to get your client’s lower leg to be perpendicular to the torso.

* For the Half-Kneeling Stretch: Stay tall through the spine and relax, but maintain an active core by drawing the abdominals inward to stabilize the lumbar region and prevent lordosis.

Coaching a client to fix anterior pelvic tilt doesn’t necessarily require a complete overhaul of their training and lifestyle. Some have minor levels of the posture, while others find themselves in serious pain and at high risk of injury. It is imperative to discern these clients from one another and properly assess them for their unique structure, skill, and intention. Then use this information to correctly assign the necessary movements to positively adapt their lives.

Photo Credit: Featured Image by Steve Jurvetson, Image 1 by Wikimedia, Image 2 by Stock Unlimited images